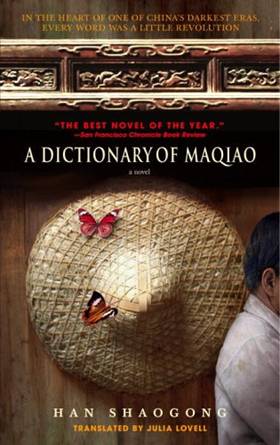

Julia Lovell translates Han Shaogong's 1998 novel, which explores the remote village to which he (or a version of such) was sent as one of the "Educated Youth" during the Cultural Revolution. The author uses the structure of dictionary entries on particular words and terms, so limited to the region and dialect, some not, to illustrate the culture he found, and gradually, as the non-alphabetical and subtly topical arrangement reveals, the stories of those who lived there. It's neither romanticized nor sensationalized. It's intellectual without sounding clever, and philosophical without losing pithiness. Lovell notes how the Tao is filtered (in some odd and creepy settings) through the last of the "Immortals" skulking about the temple ruins. You smell the stench and recoil at the sensory assault.

The novel reminded me immediately of Milorad Pavic's A Dictionary of the Khazars (1994; tr. 1988) I recall seeing this book a lot when it appeared, in the finer bookshops, but I have never heard anyone discuss it since. It boasted that the "male" and "female" editions were identical--except in one paragraph. Thanks to the Net I did not have to buy a second copy and trace each entry in tandem. The answer is here. Not sure if it matters much, and I doubt if I'll try to find out. I liked the book but was not wowed by it. Still, the predecessor in the "lexicon novel" is worth mentioning, as Shaogong's was prepared by 1995, published in 1996, and translated in 2003. Looking up this data, I learned from its Wikipedia stub: "After the book was published, some critics claimed that it violated the copyright of Pavic's novel, Dictionary of the Khazars. The author, Han Shaogong, brought a defamation case against the critics and won this case." That stub documents in turn this helpful resource of reviews.

Not an easy read, this compendium, but not beyond comprehension. This strategy's pitched at an erudite bookworm, and not a drugstore (if they still sell such) paperback. I agree with Danny Yee's site above that the narrator gets subsumed into the density of his (?) descriptions, and I repeat Lowell's admission that she could not capture a few of its 115 entries as puns, leaving them out.

And what remains, over four hundred small print pages, tends to glide past. While the "Maple Demon" and "House of Immortals" sections early on stood out, when going back to check their titles, I found that great chunks of other sections had not registered much of an impact on me. That may be my fault rather than the author or translator, but, again, this ambitious book might inevitably have some of its depth diffused in rendering it in understandable English and for an audience who did not survive the depredations of Chairman Mao and the "Down to the Countryside Movement." (Most of the above to Amazon US 11/12/17)

P.S. Lowell quotes the Sinologist A.C. Graham in her introduction to the work:

"Taoists are trying to communicate a knack, an aptitude, a way of living… [They] do not think in terms of discovering Truth or Reality. They merely have the good sense to remind us of the limitations of the language which they use to guide us towards that altered perspective on the world and that knack of living. To point the direction they use stories, verses, aphorisms, any verbal means which come to hand. Far from having no need for words, they require all available resources of literary art." I haven't been able to track online the provenance of Graham's remark so far, but it's apt.

P.P.S. I paste the start of this entry as an example of the author's strategy and scope. "*Maple Demon"

"Before I started writing this book, I hoped to write the biography of every single thing in Maqiao. I'd been writing fiction for ten or so years, but I liked reading and writing fiction less and less- I am, of course, referring to the traditional kind of fiction, which has a very strong sense of plot. Main character, main plot, main mood block out all else, dominating the field of vision of both reader and writer, preventing any sidelong glances. Any occasional casual digression is no more than a fragmentary embellishment of the main line, the temporary amnesty of a tyrant. Admittedly, there's nothing to say this kind of fiction can't approach one angle on the truth. But all you have to do is think a little, and you realize that most of the time real life isn't like that, it doesn't fit into one guiding, controlling line of cause and effect. A person often exists in two, three, four, or even more interlocking strands, outside each of which a great many other elements exist, each constituting an indispensable part of our lives. In this multifarious, scattered network of cause and effect, how valid is the domination of one main thread of protagonists, plot and mood?

Anything left out of traditional fiction is normally something of 'no significance.' But when religious authority is all-important, science has no significance; when the human race is all-important, nature has no significance. When politics is all-important, love has no significance; when money is all-important, art has no significance. I suspect the myriad things in this world are in fact all of equal importance; the only reason why sometimes one set of things seems to have 'no significance' is because they've been filtered out by the writer's view of what has significance, and dismissed by the reader's view of what has significance. They are thus debarred from all zones of potential interest. Obviously, judgement of significance is not an instinct we are born with-quite the contrary, it is no more than a function of the fashion, customs, and culture of one particular time, often revealing itself in the form into which fiction shapes us. In other words, an ideology lurks within the tradition of fiction, an ideology which reproduces itself only on passing through us.

My memory and imagination aren't totally in line with tradition.

I therefore often hope to break away from a main line of cause and effect, and look around at things that seem to have no significance whatsoever, for example contemplate a stone, focus on a cluster of stars, research a miserable rainy day, describe the random back view of someone it seems I've never met and never will meet. At the very least I should write about a tree. In my imagination, Maqiao couldn't do without a big tree. I should cultivate a tree-no, make that two trees, two maple trees-on my paper, and plant them on the slope behind Uncle Luo's house in lower Maqiao. I imagine the larger tree to be at least twenty-five meters tall, the smaller around twenty. Anyone visiting Maqiao would see from faraway the crown of the trees, the tips of whose branches would spread out to encompass a panoramic view.

This is excellent: writing the biography of two trees."

No comments:

Post a Comment