Finding in juxtaposition very divergent commentary can reveal surprising connections. These serendipitous discoveries, one of my M.A. profs warned us, did not please him when inserted into essays. He taught us Shakespeare, the Jacobeans, some recondite philosophy in truth-claims I hated, and Milton. He hated it when he'd read an academic foray that suddenly, say, for example as this was a seminar back in 1984, brought in a passage said critic had just been perusing on her pillow the night before from, say, the bestselling Stephen King yarn Pet Semetary to illustrate a passage of, I dunno, Areopagitica. The fact I had to look up what reached the NY Times top of the charts that Orwellian year shows how out of touch I was with what the Anglophone world enjoyed beyond my academia.

Nonetheless, with a shock the other day, I tallied up my own chronicle of a life spent among admittedly far less sylvan and delightfully liberal arts campus classrooms as that one in Claremont, and I figured out I'm in my thirty-sixth (I thought it was thirty-three, the age of perfection for medievals as that is when Jesus died) year of teaching. Having begun it, as a 7-12 grade sub while attending said grad school, my first year out of college, before entering UCLA that fall for my Ph.D.

I've been taken with an odd compulsion to finally read a book that helped nudge Thomas Merton towards his faith and vocation. A sign of the times when one'd pass Scribner's window display in Manhattan and see none other than Etienne Gilson's The Spirit of Mediaeval Philosophy staring back. Merton bought it. His life took the direction we know, for better as well as for his own dangers to his quest along the uneven path as a monk towards learning and folly, holy wisdom and human passion.

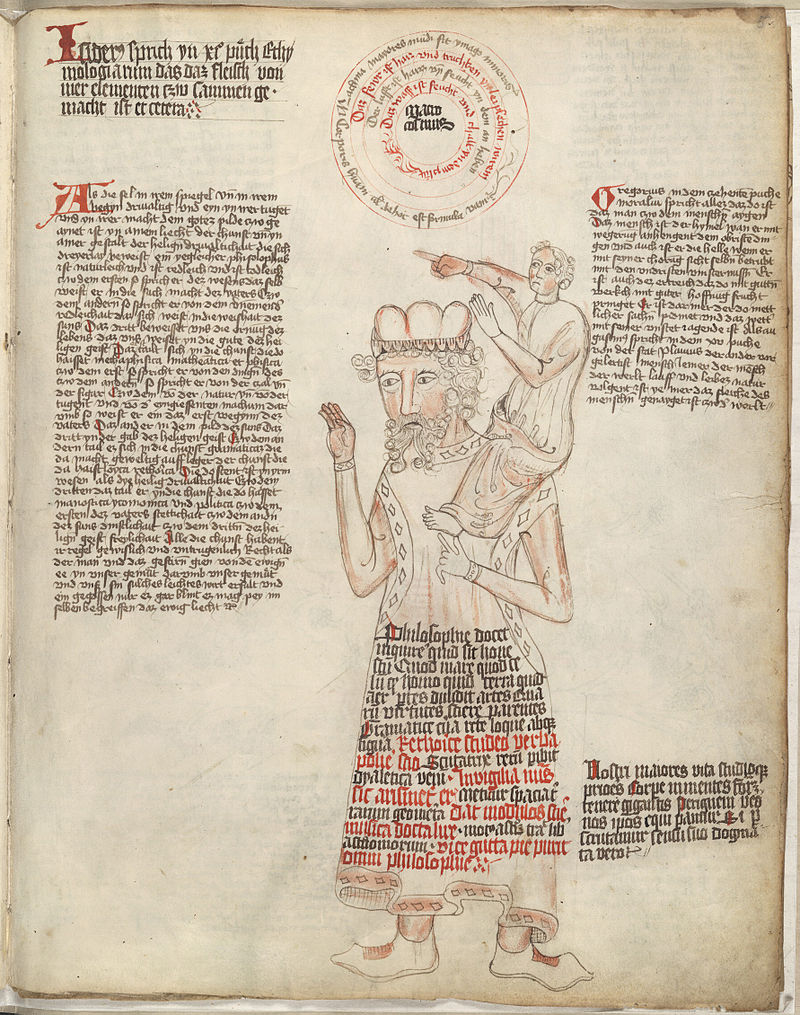

Anyhow, I had a battered secondhand copy (rescued from the UCLA Newman Cente's discard bin, tellingly, of my own collegiate era) of that 1938 translation of his Gifford Lectures given, admitted in Gilson's casual aside in the book's afterward, to an audience of non-philosophers (replete with Latin untranslated and all the erudition expected of undergrads like Merton, I suppose, of Cambridge and Columbia eminence, as well as whomever Gilson delivered his twenty talks to back in 1932 or so at Edinburgh university. To think that such a title would 1) be sold like a Stephen King novel by a bookseller 2) be bought instantly on impulse by an admittedly brilliant college student 3) furthermore comprehended by him, boggles my mind, perched as if a dwarf on the shoulders of giants, as Bernard of Chartres (living at least until 1124) is said to have invented that analogy, in the words of John of Salisbury. Of course, Gilson uses that enduring image in his own lessons, and that's a neat turnabout.

For, after having finished the lapidary construction, where no sentence sidled in as superfluous, of Gilson's study, I wanted more context on intellectual history back then. Rik Van Nieuwenhove's An Introduction to Medieval Theology filled that gap. I'd had assigned David Knowles' The Impact of Medieval Thought and Friedrich Heer's The Medieval World for respectively my Medieval Philosophy and my history of ideas in the Middle Ages undergrad electives (maybe I had a bit of Merton's aspiration in me, despite the decline of Western civ), but as for a specifically theological survey, surprisingly there's none to balance the philosophical ones of Fr Copleston, Anthony Kenny, Gilson himself, his student Armand Maurer, or the podcast-turned-popularizations of Peter Adamson.

More about what I found by that professor, who intriguingly to me teaches at tech-heavy University of Limerick, where I'd once given explored the archives by the Shannon one day, next blog posting.

No comments:

Post a Comment