A friend of Irish and Greek descent living in Germany told me today how "we need to rally together and be the keepers of all that knowledge, skills and wisdom that is needed." In a precarious economy, on a weakening planet, and within political change and cultural clashes, I look within for support. Parties fail us, "leaders" betray, and ideologies writhe. Consider the late Fidel. As his rule over Cuba consolidated as opponents were eliminated and dissent crushed, his citizens learned that saying his surname was judged disloyal. So, his first name was used, or instead, a sly gesture of stroking a chin.

So, the outpouring of grief among my leftist friends leaves me unmoved. Hearing stories of flight from that island by classmates and students, the recognition of the health and literacy reforms the Communists brought are tempered with the cruelty exercised against his foes, and innocent people such as gays, a factor little covered in the media now, as are the 500 executed by firing squad soon after the rebels became the rulers. Of course, justifications for these deeds, the broken eggs for the omelette recipe, emit as pro forma replies by the convinced and committed progressives. Fidelity.

This faithfulness joined Cubans despite their privations and losses of freedom against their foes, conjured or real. The strength of the tribe for and against what Yuval Noah Harari in

Sapiens calls "imagined fictions" enabled our ancestors to break out of their territorial and mental bonds. Then, by religion, trade, and money, ancient peoples formed nations and expanded their hold over others, too.

Imperialism has a bad name, sure. But Harari, balancing the accounts of humanity's gains and losses well in his book, warns us against too arrogant a reaction to our past. He shows the benefits of reason, while warning in his new

Homo Deus against the rush to trans-human and algorithmic domination. The cost, he argues, of transferring our humanity into information systems rub by corporations caring only about data, and not consciousness, threatens to count out the irrational, the intangible,

our ideas.

Reflecting on this, I opened an aging

NYT Sunday Review. While the recent coverage of Facebook decries its "fake news" and its implicit blame that the election was lost for Her by His minions in Macedonia planting false sites and misleading memes, the reaction from way back last May by Frank Bruni betrays a deeper concern. In

"How Facebook Warps Our Worlds" he begins: "But unseen puppet masters on Mark Zuckerberg’s payroll aren’t to blame. We’re the real culprits. When it comes to elevating one perspective above all others and herding people into culturally and ideologically inflexible tribes, nothing that Facebook does to us comes close to what we do to ourselves." While not a new phenomenon, this technology tracks us and reinforces our own prejudices and priorities.

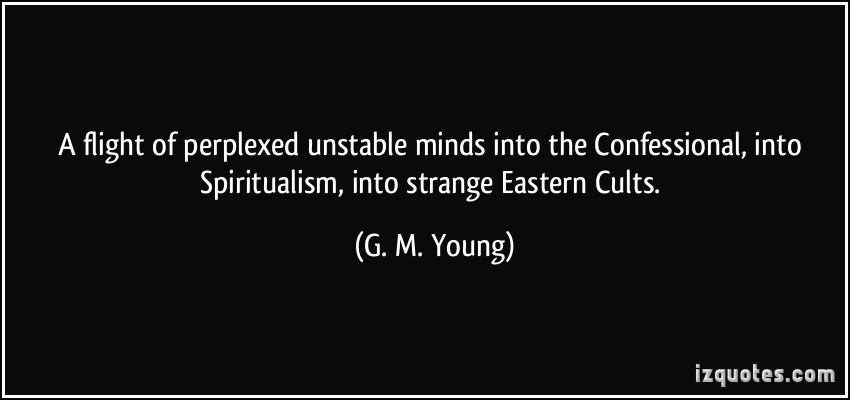

After delineating the echo chamber and referring to how we distrust institutions and so retreat to our communities of the like-minded for security, risking their scorn and aligning ourselves with their trust, Bruni decries this self-perpetuating safe space. Therefore, he concludes: "It’s not about some sorcerer’s algorithm. It’s about a tribalism that has existed for as long as humankind has and is now rooted in the fertile soil of the Internet, which is coaxing it toward a full and insidious flower."

But the blooms from FB can brighten our outlook. Today I also found in my feed from five years ago this

Salon essay from a Rutgers sociologist. Eviatar Zerubavel asks

"Why Do We Care About Our Ancestors?" Like many pieces on

Salon, it's lifted from a book so it does not read that well in part.

Still, he sums up useful perspectives that align with my own investigation of the yearning for the tribal in alternative religions claiming to remake or remodel native European spiritual traditions.

He wraps up his argument: "long before we even knew about organic evolution (or about genetics, for that matter), we were already envisioning our genealogical ties to our ancestors as well as relatives in terms of blood, thereby making them seem more natural. As a result, we also tend to regard the essentially genealogical communities that are based on them (families, ethnic groups) as natural, organically delineated communities." He notes how this "blood tie" is rooted in evolution itself.

He concludes: "Yet nature is only one component of our genealogical landscape. Culture, too, plays a critical role in the way we theorize as well as measure genealogical relatedness. Not only is the unmistakably social logic of reckoning such relatedness quite distinct from the biological reality it supposedly reflects, it oft en overrides it, as when certain ancestors obviously count more than others in the way we determine kinship and ethnicity. Relatedness, therefore, is not a biological given but a social construct. Not only are genealogies more than mere reflections of nature, they are also more than mere records of history. Rather than simply passively documenting who our ancestors were, they are the narratives we construct to actually make them our ancestors." This ties to the yearning for us to find a famous forebear (for me, all the way back to

Conchobar mac Nessa in the

Táin) at the expense of the less-heralded. But for me, that ends in 1797, as no Irish records survive before then.

This search for origins I find comforting in this chaotic world reducing us to data-mined digital data. I realize it's a romanticized quest, but not all of us find satisfaction in being reduced to Caucasian-this or white-that. Ever since I used to half-jest in school "I'm not an Anglo, I'm Irish!" I suppose I stood for this impulse. In Irish, there's more than one word for family. Tomás De Bhaldraithe (whose name shows how the Normans with Germanic nomenclature turned Gaelic in their own monikers after they invaded the island and supposedly turned more Irish than...) in his

English-Irish dictionary defines:

family, s. 1 (Members of household)

Líon m

tí, teaghlach m. Family life,

saol (an)teaghlaigh. 2 (Parents, children, relations)

Muintir f. 3 (Children)

Clann f. She is in the family way,

tá sí ag iompar clainne. How is your family?

cén chaoi bhfuil do chúram? What family have they? c

é mhéad duine clainne atá orthu? A family man,

fear tí agus urláir. 4 (Descendants)

Sliocht m (g.

sleachta),

síol m. Family tree,

craobha fpl

ginealaigh. 5 (Race)

Cine m,

treibh f. 6

Aicme f (

rudaí); Biol:

fine f. 7 Mth: Number families,

uimhirfhinte fpl. Family of sets,

cnuasach m

tacar.

So, related by blood and members of household appear to overlap, if distinguishable. Children occupy a third category, moving the clan forward in time. Descendants down the line have their own niche, and that of the race, a term we don't carry over as neatly into English, another. The term

mórtas cine or pride-in-heritage expresses this well, a reminder of the positive associations in Irish kinfolk.