Manchán Magan: Global Nomad 'as gaeilge'

Manchán Magan: Global Nomad 'as gaeilge'This Irish- speaking polyglot, peripatetic maker of documentaries with his brother, Ruan, for TnG (Teilifís na Gaeltachta: the Irish-language TV channel) and now travel writer, has been described by Roísín Ingle last August. You can read her interview (and all the other references via the link I have inserted to MM's "Global Nomad" site and related if sporadically updated blog, a plain-wrap Blogspot cousin over at "Irish Media") with this "disturbingly youthful looking encyclopedia." He's about a decade younger than yours truly, but reminds me (and resembles me a bit) of the type I might have become if I had his educational opportunities, that family lineage, and its culturally enhanced mindset. Even at a great remove, I sense that Manchán shares, at an attenuated and diasporic remove, a bit of my perspective on indigenous language, global change, and ethnic identity.

As every blurb about him states, his great-grandfather was "The O'Rahilly," one of the chivalrous rebels who waxed his moustache, kissed his pregnant wife good bye, and went off to fight and die in the Rising of 1916. His grandmother was none other than the formidable Sighle Humphries; I had no idea she had married, since a character in Thomas Flanagan's "The End of the Hunt" who I thought was based on her (if not her!) seemed a spinster devoted only to the Cause. (But that may be Dorothy Macardle, about whom has appeared a new biography.) Manchán made an RTE documentary, filed under "staged history" on the channel's site, "The Struggle," which examines the place-- a house made into a sniper's den-- as it re-creates the time with her firing away, a few sad years after the death of The O'Rahilly, at the Free Staters-- alongside Ernie O'Malley. Quite a legacy.

Which may explain this hippie-ish hermit's desire, despite his UCD degree in Irish and history, to leave Belfield's "concrete wasteland" for the 1990s countercultural, drug-addled wilds of Canada and South America. He roamed the desolate roads of Central Africa. He spent a long stint seeing visions and drinking his own urine in the Himalayas. All of these

immrami, or pilgrimages of a modern heir to St Manchán (onamastic if not paternal forebears number eight; the name's a diminutive for "monk") have appeared in print.

I hope if the author reads this he's pleased to find I have sought out at no small expense his India narrative. I am searching for his African account. (

Scriobh Manchán é seo as gaeilge amhain; ta leabhar eile aige faoi eachtrannaí na h-India go raibh ag cuireadh amach mar "Baba Ji agus TnG" le Coisceim; an bhfuil "Baba" an sceál céanna chomh sin é go bhfuil ag foilsigh mar le "Manchán's Travels"? Níl fhios agamsa.) "Angels and Rabies" appeared last year, about his earlier American adventures

as Béarla-- this title's actually stocked by Amazon US. The 1996 formation of TnG brought him, via Ruan, back to the habitual use of Irish as a medium in which to interpret the planet. The Brothers Magan film their segments in Irish and then in English, sensibly, to widen the marketability of their two dozen (to date) travelogues.

Now, he lives during the downtime with the Net but without the tube near Mullingar in a cool (literally) eco-hut. May I send my congratulations to a new near-neighbor of his and another scholarly, urbane gaeilgoir, Deaghlán, on the birth of his daughter.

Scriobh sé dom faoi Niamh, "grá geal mó chroí." His post-doc fellowship furthers his research on Conrad, terrorism, and the modern British and Irish novel. Deaghlán and Manchán would hit it off together. Manchán writes eloquently, as well as sending up (there are You Tube clips of the recent doc that made him better known, "No Béarla," that has him-- a Swiftian or at least Myles-ian mirror image of Yu Ming, ironically or fittingly given Manchán's own multi-cult cred and fluency in Chinese and five or so other tongues-- gadding about speaking Irish to crowds of uncomprehending, angry, bitter, shamed, or a few admiring native islanders) the Rising-inspired republican-induced fiction of a society that encourages daily (and damningly, governmental) use of its "first official language."

While drafting this entry, I paused. I watched the first episode of "No Béarla" (a crawl in English early on: 'we apologise for the lack of subtitles') and came away deeply ashamed. And, not only for my own stumbling in the Irish. This fatal flaw of mine can be accounted for duly. Blame my Murican mumble and my lack of Irish inculcation in my formative years halfway across the globe. Is it romanticism or remorse that colors my own disheartened reaction to viewing Manchán? His Munster-accented, loping blás makes his speech to me more easily understandable that what I encountered in Donegal-- although that Cork teacher, Áine, week two sent many of us (with all of five days previous qualifying us as vets in the mean-rang) for a dialectic loop compared to local Liam's Northwest lilt week one in our upstairs loft!

As we adults (Irish residents mixed with us foreigners) in Glencolmcille struggled against our own lack of ability, and against the neighbors' understandable if also discouraging reluctance to deal with our halting Irish in the shops, we too witnessed the counter-reaction to Irish in its eroding heartland. I can relate. Teaching ESL to Korean students currently, I could only imagine how tiring it'd be to have an endless-- at least in the high season-- parade of garbled greetings and rote exchanges with whomever walked through your store or passed you on the road. However, without such an tangibly rewarding influx as we "dia dhuit's" (as they say in Conamara of us) provide, would there still be a viable Gaeltacht at all? The Glen now counts only half of its residents as using 'an teanga beo.' The beauty of the land, the rise in holiday homes, the comfort of the EU, and the affluence of the island all fill the boreens with more imposing bungalow bliss. I think of raw concrete and dirt yards, full of jeeps and devoid of beauty, facing the rocky shores above Malin Bég.

We return to the "theme park" resentment, the reservation, the zoo animals, that so many in the heartland ridicule. However, as Angela Bourke observes, the Gaeltacht today evolves into less of a fixed location and more a "hot desk," where one check in briefly to get down to business, before commuting back home. Both natives and visitors, aided by technology and travel, can mesh electronic with sociolinguistic frontiers. Whether this can assure the survival of the habitat, as Aodan Mac Póilin warns in a related essay (in the collection "Re-Imagining Ireland," reviewed by me here recently, on Amazon US, and submitted to the online project The Blanket), remains one of our century's experiments as our planet changes.

I have written about the eco-critical component of learning Irish in its homeland in an essay:

www.estudiosirlandeses.org/Issue2/Issue%202/pdf/Eco-criticalLanguagePolitics(JMurphy).pdfCertainly, such a community may evolve at Oideas Gael. Formerly, students left the Glen and returned to forage with little sustenance at home regarding Gaelic that would fill their stimulated appetites. Now, as the director told us, we have the wealth of the Net and classes worldwide to urge our steps forward.

However, the knowledge of what we ("gabh mo leithsceal's" ["pardon me's"] as the locals at the pubs sneered sotto voce at my classmates politely entering Teacht Biddy's) "from the Irish college," (as I heard us mentioned by the lady who ran the post office and the adjoining store) represented, in our eager but self-conscious attempts to try out our phrases on the weary natives who nevertheless snapped up our euros, shows the other side of the Bord Fáilte postcard moon. The dark side-- from within what's becoming the breac-Gaeltacht, as the language retreats behind the front door out of earshot and beyond the tourist's gaze and student's garble. The shadows where Irish lingers that-- again as Maírtín Ó Cadhain's graveyard craic conjures a refined erudition and bawdy spin impossible to translate-- we "strainseíraí" or blow-ins or the most ardent (and I sat next to my share in the Glen) linguist cannot follow. They say that as a language retreats, its speakers raise up higher barriers against those who pursue it into its labyrinthine, domestic, and nested confines.

This makes me hesitate. Is Manchán's Chinese exponentially better than, say, my Irish? Of course, I assume. But, what enables some of us to better the rest of us? How nimbly does a polyglot speak his acquired languages? Are some skilled beyond mere mortals mortified like myself of making a sound, let alone a mistake? Or, do they possess some supernatural poise that enables them to assimilate. Sir Richard Burton going native in Mecca; Isabelle Eberhardt taken for an Arab boy; Tim Mackintosh-Smith chattering away in a Yemeni sub-dialect. They all gained total ease in Arabic, one of the most daunting languages. (I heard that our military gives 72 intensive weeks to gain basic skills, compared to about 20 for Spanish. It is telling that Manchán learned Arabic on his own, in his hay-bale home in faraway Westmeath.) Meanwhile, the rest of us circle or slink. Just as we have seen our peers erase blunder, overpower resistance, or conjure seduction while we gawk and stutter. Perhaps imperialism and travelogues enable this skill, or will, to power. I imagine Casanovas and Don Juans possess similar dexterity and diplomacy.

Skilled in more languages than one hand can count, Manchán returns, with mixed feelings, to the one in which he was first raised, until the age of five. Manchán's article for "Lá" laments, in strikingly plangent Irish prose, what in brusque English comes off perhaps less poignantly. In either language, he wonders if such an old method of expression has not, finally, outlived its four thousand years of North Atlantic shelf life. Steve Fallon, earlier this decade in his memoir "Home with Alice," (reviewed by me here and on Amazon US) finds parallel reactions as he-- a Bostonian and Lonely Planet guidebook writer-- tests his own acquired Irish on the Gaeltacht agus Galltacht. The language, as Liam Ó Cuinneagain, our director at Oideas Gael, told Fallon, emerge as a cyber-language even as its physical domain diminishes. Angela Bourke's essay in "Re-Imagining Ireland" maps the new century's shifting boundaries over this same psychic and also visible terrain.

I sense in Manchán as with Fallon, despite their energy and devotion, a

fin-de-seicle weariness. Should any of us try, a century after the Revival in which both sides of Manchán's family played such a leading role, to resuscitate Irish once more? Many critics doubt that adult learners can make much of a real difference; as Liam notes, it's what's heard on the playground that matters. Is Irish on life support, as "No Béarla" and "Home with Alice" appear to prove, in its native habitat? Do we let it die? Antoine Ó Flatharta, in an interview cited in Maírín Níc Eoin's lit-crit study "Trén na bhFearainn Breac," agreed with Manchán's gloomier prognosis: forget triage. Hang a toe-tag; leave the patient in peace. Euthanasia equals dying with dignity rather than the dumb-show and lip-service given it by a state in which, this month's news tells me on the Gaelport.com site, perversely, that Polish is now the true second language of the truncated Republic for which Sighle, Ernie, and The O'Rahilly dreamt and shot. Are we propping up the riddled body of Irish, as the British did James Connolly, only to face a firing squad? Not only manned by the English, but the forces of the EU, open borders, and cheap labor?

What about the resurgence, post-insurgency, of Irish among the young? Gearóid, a teacher in Dundalk, boasted about his Nigerian students who took to Gaeilge without tears, freed as they were from any of the negatives lingering among many Irish parents, past and present. The Dublin 4 crowd both participates in this interest and critiques it, apparently. Éilis Ní Dhuibhne celebrates in "Hurlamaboc" Irish as she is spoke by Malahide's texting teens. Schools teaching in Irish fill to bursting. The language, I read via Gaelport.com, is both decaying as a Leaving Cert standard and thriving as a hip BÁC lingo.

I base these varied observations on not only my own conversations and study, but upon the buzz and sales afforded the paperback by David McWilliams. A relevant excerpt appears under the "No Béarla" section on Global Nomad, about two Dublin gaeilscoileannaí. It's taken from McWilliams' pop-econ bestseller "The Pope's Children." (I could not find this in either Dublin or Belfast when I needed it to give my Ballymurphy hosts last visit-- the only copies I had seen were back at the well-stocked Four Masters Bookshop in Donegal town, a great place to spend the time waiting between buses as I did, suitcase next to me, lugging it across the Diamond for a messy but healthy repast at the organic grocer Simple Simon.)

McWilliams diminishes the practicality and dismisses the increased enrollment as a fad driven by the higher quality of Irish-medium education. But, he frames such choices within the shadows of class separation and secular independence from the clerically (if nominally) supervised traditional set-ups for schooling. Dublin 4's media have done their best to equate such schools with snobbery against immigrants and the working class. Such prejudice in the press, as a hundred years ago, often aligns a populist campaign to reclaim Irish with a contempt for progress, globalization, and anglicization. Or, today, if not capitalism-- for a century after Connolly all worship this not only in Dublin-- then a disdain for the conventional.

Manchán links to McWilliams from his page, along with a chapter from a book I reviewed on Amazon US and my blog, Ciarán Mac Murchaidh's "Who Needs Irish?" Here, Kate Fennell's equally melancholy reflections in English illuminate what Manchán expressed in Irish for "Lá": the essential personality of any language itself. Sapir-Whorf, I confess, always intrigued me. This flavor cannot be duplicated 'as Béarla'. Yet, reading about these native speakers, I glimpse how it must feel for such as Kate, Manchán, Deaghlán, and thousands of Irish who grew up speaking Irish at home. Many of their parents where not from the official Gaeltacht. Their families had learned, or passed on in Manchán's case, a hard-won decision of the previous, rebel, generation, to rouse the spirit of 1916, a dream so denigrated by not only revisionists today (and not always without reason, Kate Fennell's father's forceful rejoinders notwithstanding).

The loyal if quixotic mid-century speakers, and those who earned their

fáinne in the "jailteacht," witness the legacy of physical-force nationalism tangled with state-sponsored language reclamation. This, backfiring, flared into a guerrilla revolt against compulsory Irish and the inept manner in which it was taught and enforced. True believers, those 'cigirí agus gaeilgoirí' who pricked Myles na gCopaleen, appeared not only in the Gaeltacht but Northern cities or Dublin suburbs. Often linguistic idealism married republican ideology. For all its excess, at best I sense a sincere desire among these converts from English to Irish. They became the emblems of guilt for the Free State and then the partial Republic. They countered the relentless Anglo-American pressure to surrender. Kate's father, activist Desmond Fennell, labelled this "the Post-Western Condition"-- a consumerist malaise fueled by our 'Ameropean' masters.

But, as with Hugo Hamilton and Lorcán Ó Treasaigh in Dublin, when these citizens of the municipal Gaeltachtaí opened their front door, they faced-- reminding me of the jeers Pearse faced when reading the Proclamation at lunchtime in Easter Monday's Sackville Street-- hostility, incomprehension, or shame. They leave their school steps-- at least as dramatized in "No Béarla"-- only to find a mix of pride, antagonism, and confusion when they seek-- and have sought-- to chat on Irish streets as naturally in one native tongue as the one which you and I use to communicate now.

I hope (thinking fondly of my introduction at Oideas Gael last July to Claire, Andrew, and Caomhnait who are studying at DIT, graduates of the same city's schools that McWilliams sends up) that Deaghlán's daughter and the children of my Belfast hosts will take pride in a nimble language that can survive and thrive. If so, it is in so small measure thanks to emissaries such as Manchán. If he reads this, I send my acclaim for his efforts for TnG, his books in both

Béarla agus Gaeilge, and his desire (perhaps) not to consign Lazarus back to his grave. The O'Rahilly and Sighle Humphries and their ilk may not have had their hands totally clean when resurrecting the dying Gaul (or Gael), but they left an example for me. In more peaceful times for the island, asserting the value of what's for millennia been spoken can be done with joy and humor by all of its residents, regardless of allegiance, birthplace, or surname.

So, with my own great-grandfather a visiting Land Leaguer found-- fished lifeless from the Thames in 1898-- "in mysterious circumstances," and my own tenuous ties to the Revival retrieved this past summer, I too take hesitant heart. I go back in odd moments to the RTÉ series (reviewed by me here and on Amazon US) "Turas Teanga," turn on the subtitles in English and wish they were in Irish, and find I can follow a bit more easily what, before my fortnight's study in the Glen, eluded my fumbling comprehension. Certainly the brighter side of the moon to quench the miasma from "No Béarla"! My own travels, by the web and along the TT course, may not be as publicized or impressive as Manchán or his eloquent Irish peers, but by my own desultory gait, I try to keep up with the pace set by my own, now silent, ancestors. No matter what language we mouth, the "journey in the language" takes us back to silent thought. My longing to learn and the comfort I gain from Irish, as with English, nourishes me.

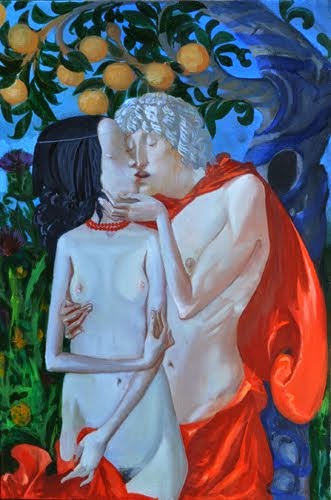

(Image: Manchán Magan and a friend in a Jordanian wadi.)