North Korea menaces again as a foe of the United States. Cuba waits as if eager for reconciliation. Regimes against which American expended much manpower and munitions fifty years ago now trade with their neighbors in Asia, the largest of which, China, is capitalist in fact if not theory. Headlines and Wiki-Leaks pepper the news and feeds with distrust of a sinister Russia, echoing the Cold War.

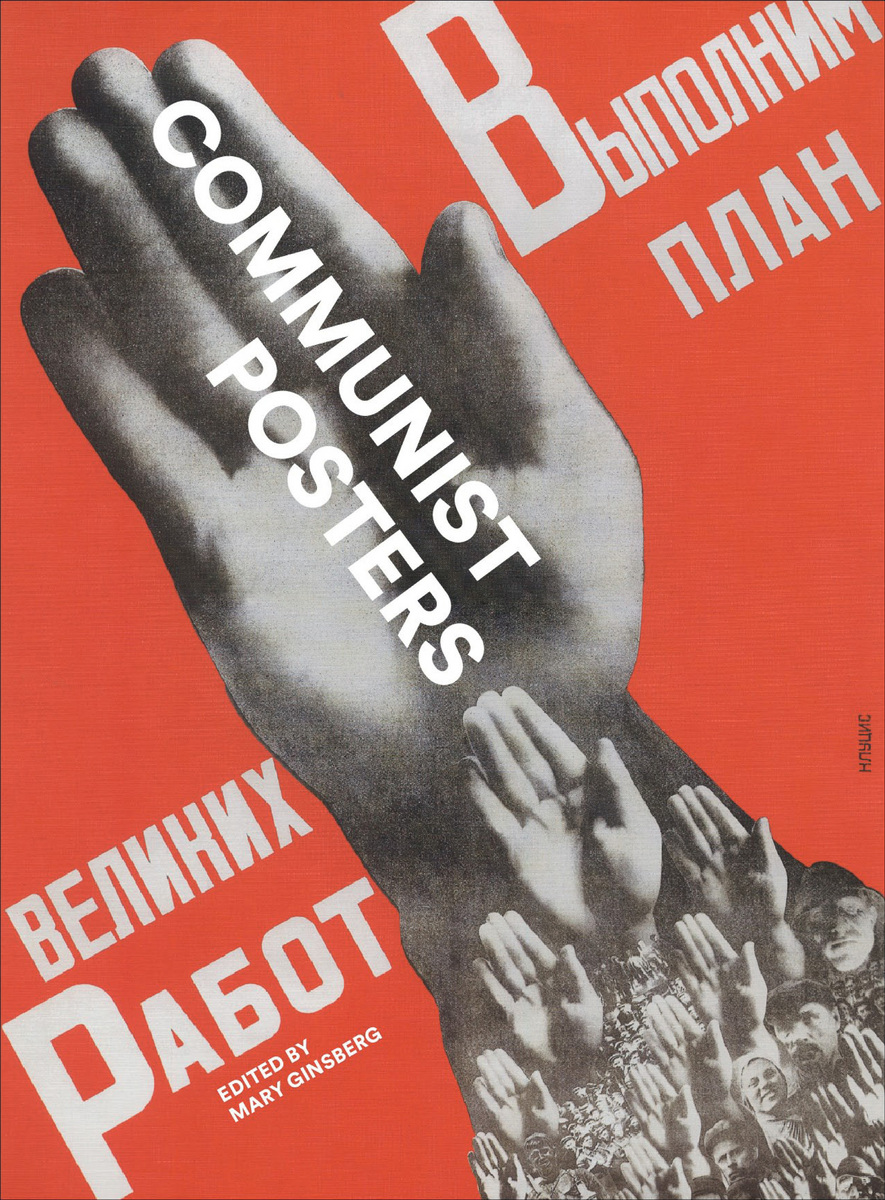

This range of reactions by the U.S. government and media to Communist nations makes this collection of posters from these and allied nations under red flags relevant. On the centenary of the Bolshevik Revolution, Mary Ginsberg edits and introduces the most comprehensive presentation in print of often vivid propaganda, that for a less screen-focused century, captured the eyes and the minds of hundreds of millions. They celebrated, endured, or hated the heydays of Fidel or Mao, Lenin and Stalin and the various apparatchiks who tried to implement their theories and schemes.

A representative example appears early on. Red Loudspeakers Are Sounding Through Every Home (1972), as Ginsberg observes, documents the use of images to instill obedience. In a Chinese village, slogans, songs and lectures emanate from speakers installed on the streets. Their indoctrination may have seemed inescapable. For such broadcasts cannot be shut off. Other means further the deification of the leader as well as his dictates. The home shown on the poster has only a framed portrait of The Chairman, surrounded by small banners with sayings and little red books. Outside, a family gathers.

Over 330 illustrations demonstrate the range and the scope beyond the U.S.S.R. and the P.R.C., Korean, Mongolian, Eastern European, Vietnamese and Cuban chapters provide essays by scholars. These cross-reference the pictures, providing a narrated guided tour that alerts readers to the themes.

These depend heavily on Constructivism and photomontage. Art as function and promotion through photography combine to sell the peasants and workers on these products of the intellectuals. What they peddle are exhortations to produce more, fight harder and act braver. The verbosity of the caption can weigh down the impact of the 1937 image. Sergei Igumnov's red fist emerging from the rolled-up sleeve showing off a worker's clenched and muscular arm strangles a snake with swastika eyes. What this depicts is: "We'll Uproot Spies and Deviationists of the Trotsky-Bukharin Agents of Fascism." Given the relentless purges under the Man of Steel, such creations linger longer for their visual force rather than the ever-changing explanations linking the art to the enemy of the moment.

As dynasties bore down, the masses viewed ideals. Aleksei Lavrov's The People's Dreams Have Come True (1950) has a grandfather resembling Lenin. He clasps a Young Pioneer's shoulder. The old man's smile encourages the slightly wistful, perhaps hesitant, fantasies of the boy, looking up from his book, penned by "a critic of urban social conditions." Pravda sits on the table of their ship's cabin. Behind their sofa a reproduction of "the famous Repin painting Barge Haulers on the Volga" is a bit blurred, but "confirming how terrible things used to be." Outside, ships sail past factories that gleam.

The last Soviet poster blurs into patterns mirroring 1920s abstractions. Other lands drew on their own artistic legacies. Mongolian folk art and calligraphy enter many of its first efforts, while later ones mimic the Chinese Communist preference for red banners, gesticulating vanguards, rosy cheeks and marching masses. Polish aesthetics, as evocatively shown on film posters, also grace political ones.

Silhouettes, shadows, stark typefaces and surreal figures shunted aside the Soviet template. Czech and Hungarian designers likewise incorporated pop art and psychedelic patterns into silkscreen and montage takes on opera, a new television model or Allende's brief Chilean victory. Anti-Americanism also heightens for Western audiences a Chinese imitation of an anti-Vietnam war mural, with placards of English-language denunciations of the war machine. North Korea dutifully perpetuates this type.

The appeal of stylized "characters in primary colors, along with shrill slogans, dotted with exclamation marks" predates the reign of Kim Il Sung. But their "visual recognizability and readability" sustain themselves for two-thirds of a century due to the simple, even atrophied graphics. As Koen de Ceuster explains in this section, campaigns prove unrelenting under the Kims, and so the shelf life of a given poster is limited: "the message prevails over the package." He also asks a necessary question: "Where does art end and propaganda begin?" For the D.P.R.K., art theory combines ideological with artistic equality through a unified concept. Agitprop exhorts the Koreans to work diligently against an Uncle Sam whose competing tanks, bombers and missiles always loom.

What distinguishes Korean versions is a frequent inclusion of a mythical horse flying over smoking chimneys and rice paddies. Eyes also lead the way as they flare up and as fingers point the way on.

Vietnam takes French and Indochinese influences, hand-drawn lettering, indigenous themes and guerrilla poses from street art for some of its varied products. They stand out as more awkward and more original than the Soviet, Maoist or Korean contributions. They perpetuate the raw, eyewitness sensibility of not an imagined but a real struggle against an imperialist invader, or more than one.

Another rich array of approaches results in Cuban artifacts. International influences entered into the island's art long before 1959. Capitalizing on tourism and a worldwide market, its posters were sold as commercial items. Diminishing the Socialist Realism quotient, they increase the use of stencils, hand-cut and silkscreened. Disparate objects may juxtapose; so may "humour and visual wit." Not to mention Castro's 1977 proclamation: "Our enemy is imperialism, not abstract art." Contrasting the sophistication of the Cuban propaganda against the simplicity of Mongolian, for instance, reminds viewers and readers of the connections one Communist enclave may enjoy, as opposed to another.

One closes this collection wondering what the future holds for political posters. Capitalist systems appeal to the watcher of a screen far more than the passerby of a placard. Scholars in this current century may have to hope that our soon-outmoded digital technology records the catchphrases and memes generated by the political spectrum today as carefully as archivists have these bold posters. (Spectrum Culture 12/1/17 with slight changes) 432 pages 04-22-17 Reaktion Books

A representative example appears early on. Red Loudspeakers Are Sounding Through Every Home (1972), as Ginsberg observes, documents the use of images to instill obedience. In a Chinese village, slogans, songs and lectures emanate from speakers installed on the streets. Their indoctrination may have seemed inescapable. For such broadcasts cannot be shut off. Other means further the deification of the leader as well as his dictates. The home shown on the poster has only a framed portrait of The Chairman, surrounded by small banners with sayings and little red books. Outside, a family gathers.

Over 330 illustrations demonstrate the range and the scope beyond the U.S.S.R. and the P.R.C., Korean, Mongolian, Eastern European, Vietnamese and Cuban chapters provide essays by scholars. These cross-reference the pictures, providing a narrated guided tour that alerts readers to the themes.

These depend heavily on Constructivism and photomontage. Art as function and promotion through photography combine to sell the peasants and workers on these products of the intellectuals. What they peddle are exhortations to produce more, fight harder and act braver. The verbosity of the caption can weigh down the impact of the 1937 image. Sergei Igumnov's red fist emerging from the rolled-up sleeve showing off a worker's clenched and muscular arm strangles a snake with swastika eyes. What this depicts is: "We'll Uproot Spies and Deviationists of the Trotsky-Bukharin Agents of Fascism." Given the relentless purges under the Man of Steel, such creations linger longer for their visual force rather than the ever-changing explanations linking the art to the enemy of the moment.

As dynasties bore down, the masses viewed ideals. Aleksei Lavrov's The People's Dreams Have Come True (1950) has a grandfather resembling Lenin. He clasps a Young Pioneer's shoulder. The old man's smile encourages the slightly wistful, perhaps hesitant, fantasies of the boy, looking up from his book, penned by "a critic of urban social conditions." Pravda sits on the table of their ship's cabin. Behind their sofa a reproduction of "the famous Repin painting Barge Haulers on the Volga" is a bit blurred, but "confirming how terrible things used to be." Outside, ships sail past factories that gleam.

The last Soviet poster blurs into patterns mirroring 1920s abstractions. Other lands drew on their own artistic legacies. Mongolian folk art and calligraphy enter many of its first efforts, while later ones mimic the Chinese Communist preference for red banners, gesticulating vanguards, rosy cheeks and marching masses. Polish aesthetics, as evocatively shown on film posters, also grace political ones.

Silhouettes, shadows, stark typefaces and surreal figures shunted aside the Soviet template. Czech and Hungarian designers likewise incorporated pop art and psychedelic patterns into silkscreen and montage takes on opera, a new television model or Allende's brief Chilean victory. Anti-Americanism also heightens for Western audiences a Chinese imitation of an anti-Vietnam war mural, with placards of English-language denunciations of the war machine. North Korea dutifully perpetuates this type.

The appeal of stylized "characters in primary colors, along with shrill slogans, dotted with exclamation marks" predates the reign of Kim Il Sung. But their "visual recognizability and readability" sustain themselves for two-thirds of a century due to the simple, even atrophied graphics. As Koen de Ceuster explains in this section, campaigns prove unrelenting under the Kims, and so the shelf life of a given poster is limited: "the message prevails over the package." He also asks a necessary question: "Where does art end and propaganda begin?" For the D.P.R.K., art theory combines ideological with artistic equality through a unified concept. Agitprop exhorts the Koreans to work diligently against an Uncle Sam whose competing tanks, bombers and missiles always loom.

What distinguishes Korean versions is a frequent inclusion of a mythical horse flying over smoking chimneys and rice paddies. Eyes also lead the way as they flare up and as fingers point the way on.

Vietnam takes French and Indochinese influences, hand-drawn lettering, indigenous themes and guerrilla poses from street art for some of its varied products. They stand out as more awkward and more original than the Soviet, Maoist or Korean contributions. They perpetuate the raw, eyewitness sensibility of not an imagined but a real struggle against an imperialist invader, or more than one.

Another rich array of approaches results in Cuban artifacts. International influences entered into the island's art long before 1959. Capitalizing on tourism and a worldwide market, its posters were sold as commercial items. Diminishing the Socialist Realism quotient, they increase the use of stencils, hand-cut and silkscreened. Disparate objects may juxtapose; so may "humour and visual wit." Not to mention Castro's 1977 proclamation: "Our enemy is imperialism, not abstract art." Contrasting the sophistication of the Cuban propaganda against the simplicity of Mongolian, for instance, reminds viewers and readers of the connections one Communist enclave may enjoy, as opposed to another.

One closes this collection wondering what the future holds for political posters. Capitalist systems appeal to the watcher of a screen far more than the passerby of a placard. Scholars in this current century may have to hope that our soon-outmoded digital technology records the catchphrases and memes generated by the political spectrum today as carefully as archivists have these bold posters. (Spectrum Culture 12/1/17 with slight changes) 432 pages 04-22-17 Reaktion Books

No comments:

Post a Comment