Back in the early '80s, I bought Shusaku Endo's novel Sílence. Finally issued in paperback, and with me enrolled at a Jesuit university, I rushed to savor it. A harrowing novel (see my linked review), this angered at least on Amazon the likes of sensitive Catholics unable to accept that a priest under pressure after witnessing the torture and death of others who died for one's presence might succumb.

The end of that same decade, Martin Scorsese read it. It was recommended by New York's Episcopal bishop in the wake of the controversy over his adaptation of another controversial work, The Last Temptation of Christ. Marty vowed to make it a movie, if he could figure out how to capture its hold.

He did, and as the scholar of American Catholicism Paul Elie's The Passion of Martin Scorsese in The New York Times Magazine observes: the book and the film join well. For the subject "locates, in the missionary past, so many of the religious matters that vex us in the postsecular present — the claims to universal truths in diverse societies, the conflict between a profession of faith and the expression of it, and the seeming silence of God while believers are drawn into violence on his behalf." Elie locates in the filmmaker's oeuvre a pursuit of the "poisoned arrow of religious conflict" and poison indeed surfaces in the film. I saw it at a premiere in Westwood, a block from the bookstore where I found the novel decades ago. The excitement of seeing this in the Regency, a cavernous 1931 Art Deco palace filled with maybe a thousand people, was palpable, for the director would be there for a panel afterwards. But I was unsure if many there knew what a story they'd face.

Face, as the image of Christ, in the film as Scorsese explained taken from El Greco --for the original work's use of Piero della Francesca did not transfer to the big screen when tested-- confides a human trust in its viewer, that He would accompany its beholder through whatever moral perils lay ahead. The divinity of Jesus is of course in Christian orthodoxy inseparable from his humanity, but for the director, the eyes had it. They convey the distance and the direction proper to a bold Jesuit follower.

The film itself, 2:40, unfolded slowly. It was difficult for me to gain full immersion as a woman two seats down connected as she proclaimed to the producer checked her smartphone regularly, and a man behind me kept chuckling at dramatic moments perhaps taken by the nervous or shallow as comedy. There is a bit of levity, in the tragic Judas-figure of Kichijiro keeps popping up at tense moments begging for the protagonist Fr. Sebastian Rodrigues' confession, Yet that moved me, not to laughter, but to their poignant bond, which gains significance as the narrative turns to the priest's struggles.

That Japanese convert-traitor asks where is the place for a weak man in this world. A common plaint. Scorsese's vision raises up Rodrigues as an alter Christus in Passion Play form, entering twice cities on a donkey while being pelted with stones and abuse. I suppose this fits, on the other hand, any priest. Yet the acting skills and the power of the necessarily didactic script by Jay Cocks and Scorsese project Endo's investigation well. As a child he was baptized, and he questioned here and in The Samurai (set among Franciscans of the Mexican conquest) the ability of a foreign people to truly give in to an invader, or a promise of liberation for the poor within a peaceful and carefree paradise, when the basic tenets of this faith were garbled, as the "Son of God" comes rendered from their native Sun.

As Rodrigues replies, that land is poisoned. Nothing can grow there, the Japanese powers reason, as all rots in this island swamp. The tension between apostasy and martyrdom, fidelity and surrender tightens the energy. Early on, all is painterly fog in the cold and chilly islands where the renegade Christians have gone underground as relentless crackdowns have reduced the 300,000-strong community in the wake of St. Francis Xavier to a remnant, hunted down and all burnt or drowned.

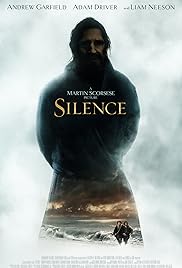

Later, in Nagasaki, clarity returns, amidst the regimented architecture, ranks, and sumptuary distinctions. Rodrigues' predecessor, Ferrara, speaks eloquently for moral compromise, to spare pain. As their translator adds, no man should take away another's spirit. I watched this with engagement. I presume it may not have swayed all (my wife advised cutting twenty minutes and squirmed at the debates I found in jesuitical tutelage as fascinating and stimulating). But as Scorsese mentioned in the after-film panel (joined by production designer Dante Ferretti, actors Liam Neeson, Adam Driver, Andrew Garfield, Issei Ogata, editor Thelma Schoonmaker, and producer Irwin Winkler--and a fawning host who called the director "Maestro"), he hoped the film would bring "peace of mind."

I second his ambition. Elie's skillful article locates the film within the inculturation aims of imperialism and religious missions. (But he overlooks as do many that the novel was translated by a Belfast Jesuit, Fr. William Johnston, who taught at Sophia University run by the Society in Tokyo, and who himself embraced Zen.) Do we insist the newcomers to a practice go over to the practices of the faith? Or as the Jesuits did in China, do we accommodate the faith to indigenous folkways and traditions? St. Boniface, when he preached to the Frisians in the 8th century, was told he should not destroy the temples and groves, but make them into centers of worship and pilgrimage for a new generation. Clever, as this supplants rather than terminates the sacred connection. But the fervent and fundamentalists may refuse compromise, and thus this challenging film and novel remain relevant.

As Pope Francis, the first Jesuit installed in the Vatican as such, told Scorsese on the film's first showing in Rome, may the film bear much fruit. That's a message all of us can applaud, this season.

No comments:

Post a Comment