The Irish writer born as Brian Ó Nualláin and best known under one of his many assumed names as Flann O'Brien has long been championed as a harbinger of post-modernism. Literary scholars scrutinized his life as a Dublin newspaperman and his relatively few fictional publications as proof of his eccentric genius, if as a talent overshadowed by a predecessor he both cultivated and resented, James Joyce. Their conventional wisdom lamented Brian O'Nolan the journalist/ O'Brien the fabulist as succumbing to ennui, drink, and hackwork, squandering subversive skills premiered in the novels

At Swim-Two-Birds and

The Third Policeman at the end of the 1930s. His modernist credentials, by contrast, have often been diminished.

So claim the fourteen participants from a University of New South Wales seminar commemorating the 2011 centenary of O'Brien's birth. Choosing not to focus on his life as Brian O'Nolan but on his works under many names, usually that of Flann O'Brien, professors expand their papers into academic essays. As with Maebh Long's "

Assembling Flann O'Brien" (reviewed by me as "Making Sense of Nonsense", 14 April 2014) from the same publisher earlier this year, a reader may wonder what the author, who so gleefully and bitterly lampooned scholarship, would make of so many studious, posthumous tributes.

As co-editor Rónán McDonald explains, Brian O'Nolan's works elude genre conventions. O'Nolan's refusal to stay pinned down transcends his career as a civil servant in Dublin during the middle of the last century. His occupation impelled his taking on other names to disguise his mockery of the Irish government, its bureaucracy, and their mission to make the Irish language one that English-speaking natives would be compelled to learn. Furthermore, O'Brien, who as Myles na gCopaleen also penned witty columns for the

Irish Times, ridiculed his nation's clerical and lay authorities, the humbugs and scolds around him, and the dull "Plain People of Ireland". He refined this raw material by savage wit.

McDonald introduces his essay on

The Third Policeman's nihilism by summing him up: "His views and attitudes are shrouded in irony, ambiguity, linguistic play, ingenious obfuscation. There is abundant satire in his novels, as in his journalism, though the po-faced scholasticism of Flann contrasts with the populist posture of Myles. He lampoons patriotic Gaels in

An Béal Bocht, the mythologies of the Irish Revival in

At Swim-Two-Birds, finicky academicians in

The Third Policeman." He loved to put down pretentiousness but he shied away from confrontation. Flann was more bold than Myles; his various personae masked his eccentricities even as they encouraged them.

Certainly, as contributors emphasize, O'Brien's disguises allowed him to sidle into arcane and odd controversies which he incorporated into his experimental fiction. Sean Pryor examines the influence of St. Augustine, and how good needs evil so God's creations can appreciate better their happy times; John Attridge compliments this approach with a study of O'Brien's use of Augustine of Hippo. He is a central character as is James Joyce, both in altered form, in O'Brien's last novel,

The Dalkey Archive, published two years before O'Nolan's death in 1966. Augustinian notions of "sociable lies" reveal a slippery quality, in ethics as well as characterization, which warps scholastic satire into twisted plots.

Instability inspires the next three essays. Stefan Solomon investigates the relative failure of O'Brien's theatrical efforts to convey what in

At Swim-Two-Birds succeeded as a subversive revolt of its tetchy characters against their scheming author. Solomon and Stephen Abbitt, regarding Flann's tribute to and travesty of James Joyce, agree that O'Brien emerges as a "reluctant modernist", contrary to most academic predecessors who have preferred to situate him among post-modernist literary pioneers.

However, as David Kelly insists, O'Nolan's many guises shared an "innate faculty for finding things funny", anticipating the post-modernist, mid-twentieth century "literature of exhaustion". Flann's repetition of his material attests to his living late enough to deal with the trauma of the past century in a more detached, obsessive, and playful manner. After all, he did not have to relive the difficulties of the early century, Kelly avers. In his ludicrous and bizarre creations, Flann is instead a harbinger of his century's "generational shift" away from recreating torment. Instead, post-modernist authors tend to mock, invert, and tease the pain of isolation and the power of obsession, through parody or irony.

These selections examine certain works from O'Nolan's varieties of names and works, but they bypass many others. The three novels cited above by McDonald garner most attention, but

The Hard Life: An Exegesis of Squalor (1961), considered his weakest novel, gets two asides. As with Myles' prolific newspaper columns, under-examined here, a study of the strained attempts at satire in O'Nolan's later career, writing as Flann, might have balanced the general acclaim granted by contributors to his successful works. One needs to know where and how O'Nolan lost the plot.

The next set of entries roam into the linguistic methods employed by Flann O'Brien. Maebh Long repeats some material from her recent book. She focuses here upon

An Béal Bocht, to show how Flann's use of the Irish language addresses, or subverts, vexing preoccupations of naming and identity among conflicting Irish-speaking cohorts. Long compares Patrick Powers' 1973 translation as

The Poor Mouth of this novel, by Myles na gCopaleen; her essay ends a bit eccentrically, if fittingly for this material, which evades cohesion even for the Irish-fluent reader, undoubtedly as its intention.

A peer of O'Nolan's, the poet Patrick Kavanagh, also jeered at the Irish government's propaganda about the doughty Gaelic peasant. Joseph Brooker compares Kavanagh's approach with O'Brien's. Kavanagh and O'Brien's predecessors, Samuel Beckett and Joyce, connect via O'Nolan's marginalia in his copies of their works, as Dirk Van Hulle explains. These authors share an interest in parallax, "Chinese boxes" as nested narratives, and regression in theme and structure in their literary creations.

Regression and mathematical patterns via numerology in

At Swim-Two-Birds, as Baylee Brits demonstrates, document O'Brien's scientific and technological interests, in the next section of essays. The coupling of mechanical devices and eerie inventions within

The Third Policeman, as McDonald shows, represents darker corners of O'Brien's textual labyrinths, which continue to disorient readers.

The pull into infinity and regression reveals the abysmal and the dismal; co-editor Julian Murphet charts the tension between Myles the journalist and Flann the fabulist as he conjures up pataphysics and other esoteric send-ups of rational analysis, within O'Brien's fictions exposing a psychic death drive. The compulsions many of his characters exhibit pushes their pursuits beyond entertainment.

This aspect, the haunted quality within this troubled writer, does not earn the biographical context which Anthony Cronin's 1989 biography,

No Laughing Matter, treated with compassion and insight. But, readers familiar with O'Brien's life and works already (a prerequisite, as little more than a nod to this background is given by the contributors or editors) will learn from Sam Dickson about Flann's propensity for fictions full of "hard drink". This compliments co-editor Sascha Morrell's congenial foray, as she aligns O'Brien's treatment of alcohol with the Australian writer Frank Moorhouse's

The Electrical Experience: A Discontinuous Narrative (1974), about a soft drink maker Down Under. Culture and commodity feature here and in the final two, atypically off-beat (even by O'Nolan's standards) essays revealing Flann's range and curiosity.

Mark Steven examines "aestho-autonomy" through

At Swim-Two-Birds' Dermot Trellis. Trellis seeks solitude, to pursue masturbation. Steven frames this ambition as a "formal and narrative act", thus indicative of the political and economic stagnation in the new Irish Free State for which O'Nolan labored. Physical exertion, onanism, gender roles, and male potency also seeped into none other than the bicycle seat, as that machine and its rider merged, in O'Brien's

The Third Policeman in forms that this short review cannot elucidate. Suffice to say that these learned essays may encourage the reader to take down O'Brien from the bookshelf. After perusing the ruminations of a coterie of his critics, why not enter, for the first time or another time, into the fictions of Flann O'Brien, Myles na gCopaleen, and various odd characters his writer wrote as, and about? The Irish labyrinth awaits you. (10-1-14 to

PopMatters)

Chapter 1 Making Evil, with Flann O’Brien

Sean Pryor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 2 Mythomaniac modernism: lying and bullshit in Flann O’Brien

John Attridge, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 3 ‘The outward accidents of illusion’: O’Brien and the Theatrical

Stefan Solomon, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 4 The Ghost of ‘Poor Jimmy Joyce’: A Portrait of the Artist as a Reluctant Modernist

Stephen Abblitt, La Trobe University, Australia

Chapter 5 ‘Do You Know What I’m Going to Tell You?’: Flann O’Brien, Risibility and the Anxiety of Influence

David Kelly, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 6 An Béal Bocht, Translation and the Proper Name

Maebh Long, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Chapter 7 Ploughmen Without Land: Flann O’Brien and Patrick Kavanagh

Joseph Brooker, University of London, United Kingdom

Chapter 8 Flann O’Brien’s Ulysses: Marginalia and the Modernist Mind

Dirk Van Hulle, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Chapter 9 ‘Truth is an Odd Number’: Flann O’Brien and Infinite Imperfection

Baylee Brits, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 10 ‘An astonishing parade of nullity’: Nihilism in The Third Policeman

Rónán McDonald, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 11 Flann O’Brien and Modern Character

Julian Murphet, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 12 ‘No unauthorized boozing’: Flann O’Brien and the Thirsty Muse

Sam Dickson

Chapter 13 Soft drink, hard drink, and literary (re)production in Flann O’Brien and Frank Moorhouse

Sascha Morrell, University of New England, Australia

Chapter 14 Flann O’Brien’s Aestho-Autogamy

Mark Steven, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 15 Modernist Wheelmen

Mark Byron, University of Sydney, Australia - See more at: http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/flann-obrien-modernism-9781623568504/#sthash.Z1ncj15a.dpu

Chapter 1 Making Evil, with Flann O’Brien

Sean Pryor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 2 Mythomaniac modernism: lying and bullshit in Flann O’Brien

John Attridge, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 3 ‘The outward accidents of illusion’: O’Brien and the Theatrical

Stefan Solomon, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 4 The Ghost of ‘Poor Jimmy Joyce’: A Portrait of the Artist as a Reluctant Modernist

Stephen Abblitt, La Trobe University, Australia

Chapter 5 ‘Do You Know What I’m Going to Tell You?’: Flann O’Brien, Risibility and the Anxiety of Influence

David Kelly, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 6 An Béal Bocht, Translation and the Proper Name

Maebh Long, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Chapter 7 Ploughmen Without Land: Flann O’Brien and Patrick Kavanagh

Joseph Brooker, University of London, United Kingdom

Chapter 8 Flann O’Brien’s Ulysses: Marginalia and the Modernist Mind

Dirk Van Hulle, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Chapter 9 ‘Truth is an Odd Number’: Flann O’Brien and Infinite Imperfection

Baylee Brits, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 10 ‘An astonishing parade of nullity’: Nihilism in The Third Policeman

Rónán McDonald, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 11 Flann O’Brien and Modern Character

Julian Murphet, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 12 ‘No unauthorized boozing’: Flann O’Brien and the Thirsty Muse

Sam Dickson

Chapter 13 Soft drink, hard drink, and literary (re)production in Flann O’Brien and Frank Moorhouse

Sascha Morrell, University of New England, Australia

Chapter 14 Flann O’Brien’s Aestho-Autogamy

Mark Steven, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 15 Modernist Wheelmen

Mark Byron, University of Sydney, Australia - See more at: http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/flann-obrien-modernism-9781623568504/#sthash.Z1ncj15a.dpuf

Chapter 1 Making Evil, with Flann O’Brien

Sean Pryor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 2 Mythomaniac modernism: lying and bullshit in Flann O’Brien

John Attridge, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 3 ‘The outward accidents of illusion’: O’Brien and the Theatrical

Stefan Solomon, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 4 The Ghost of ‘Poor Jimmy Joyce’: A Portrait of the Artist as a Reluctant Modernist

Stephen Abblitt, La Trobe University, Australia

Chapter 5 ‘Do You Know What I’m Going to Tell You?’: Flann O’Brien, Risibility and the Anxiety of Influence

David Kelly, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 6 An Béal Bocht, Translation and the Proper Name

Maebh Long, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Chapter 7 Ploughmen Without Land: Flann O’Brien and Patrick Kavanagh

Joseph Brooker, University of London, United Kingdom

Chapter 8 Flann O’Brien’s Ulysses: Marginalia and the Modernist Mind

Dirk Van Hulle, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Chapter 9 ‘Truth is an Odd Number’: Flann O’Brien and Infinite Imperfection

Baylee Brits, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 10 ‘An astonishing parade of nullity’: Nihilism in The Third Policeman

Rónán McDonald, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 11 Flann O’Brien and Modern Character

Julian Murphet, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 12 ‘No unauthorized boozing’: Flann O’Brien and the Thirsty Muse

Sam Dickson

Chapter 13 Soft drink, hard drink, and literary (re)production in Flann O’Brien and Frank Moorhouse

Sascha Morrell, University of New England, Australia

Chapter 14 Flann O’Brien’s Aestho-Autogamy

Mark Steven, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 15 Modernist Wheelmen

Mark Byron, University of Sydney, Australia - See more at: http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/flann-obrien-modernism-9781623568504/#sthash.Z1ncj15a.dpuf

Chapter 1 Making Evil, with Flann O’Brien

Sean Pryor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 2 Mythomaniac modernism: lying and bullshit in Flann O’Brien

John Attridge, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 3 ‘The outward accidents of illusion’: O’Brien and the Theatrical

Stefan Solomon, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 4 The Ghost of ‘Poor Jimmy Joyce’: A Portrait of the Artist as a Reluctant Modernist

Stephen Abblitt, La Trobe University, Australia

Chapter 5 ‘Do You Know What I’m Going to Tell You?’: Flann O’Brien, Risibility and the Anxiety of Influence

David Kelly, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 6 An Béal Bocht, Translation and the Proper Name

Maebh Long, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Chapter 7 Ploughmen Without Land: Flann O’Brien and Patrick Kavanagh

Joseph Brooker, University of London, United Kingdom

Chapter 8 Flann O’Brien’s Ulysses: Marginalia and the Modernist Mind

Dirk Van Hulle, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Chapter 9 ‘Truth is an Odd Number’: Flann O’Brien and Infinite Imperfection

Baylee Brits, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 10 ‘An astonishing parade of nullity’: Nihilism in The Third Policeman

Rónán McDonald, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 11 Flann O’Brien and Modern Character

Julian Murphet, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 12 ‘No unauthorized boozing’: Flann O’Brien and the Thirsty Muse

Sam Dickson

Chapter 13 Soft drink, hard drink, and literary (re)production in Flann O’Brien and Frank Moorhouse

Sascha Morrell, University of New England, Australia

Chapter 14 Flann O’Brien’s Aestho-Autogamy

Mark Steven, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 15 Modernist Wheelmen

Mark Byron, University of Sydney, Australia - See more at: http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/flann-obrien-modernism-9781623568504/#sthash.Z1ncj15a.dpuf

Chapter 1 Making Evil, with Flann O’Brien

Sean Pryor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 2 Mythomaniac modernism: lying and bullshit in Flann O’Brien

John Attridge, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 3 ‘The outward accidents of illusion’: O’Brien and the Theatrical

Stefan Solomon, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 4 The Ghost of ‘Poor Jimmy Joyce’: A Portrait of the Artist as a Reluctant Modernist

Stephen Abblitt, La Trobe University, Australia

Chapter 5 ‘Do You Know What I’m Going to Tell You?’: Flann O’Brien, Risibility and the Anxiety of Influence

David Kelly, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 6 An Béal Bocht, Translation and the Proper Name

Maebh Long, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Chapter 7 Ploughmen Without Land: Flann O’Brien and Patrick Kavanagh

Joseph Brooker, University of London, United Kingdom

Chapter 8 Flann O’Brien’s Ulysses: Marginalia and the Modernist Mind

Dirk Van Hulle, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Chapter 9 ‘Truth is an Odd Number’: Flann O’Brien and Infinite Imperfection

Baylee Brits, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 10 ‘An astonishing parade of nullity’: Nihilism in The Third Policeman

Rónán McDonald, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 11 Flann O’Brien and Modern Character

Julian Murphet, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 12 ‘No unauthorized boozing’: Flann O’Brien and the Thirsty Muse

Sam Dickson

Chapter 13 Soft drink, hard drink, and literary (re)production in Flann O’Brien and Frank Moorhouse

Sascha Morrell, University of New England, Australia

Chapter 14 Flann O’Brien’s Aestho-Autogamy

Mark Steven, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 15 Modernist Wheelmen

Mark Byron, University of Sydney, Australia - See more at: http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/flann-obrien-modernism-9781623568504/#sthash.58blLTNi.dpuf

Chapter 1 Making Evil, with Flann O’Brien

Sean Pryor, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 2 Mythomaniac modernism: lying and bullshit in Flann O’Brien

John Attridge, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 3 ‘The outward accidents of illusion’: O’Brien and the Theatrical

Stefan Solomon, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 4 The Ghost of ‘Poor Jimmy Joyce’: A Portrait of the Artist as a Reluctant Modernist

Stephen Abblitt, La Trobe University, Australia

Chapter 5 ‘Do You Know What I’m Going to Tell You?’: Flann O’Brien, Risibility and the Anxiety of Influence

David Kelly, University of Sydney, Australia

Chapter 6 An Béal Bocht, Translation and the Proper Name

Maebh Long, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Chapter 7 Ploughmen Without Land: Flann O’Brien and Patrick Kavanagh

Joseph Brooker, University of London, United Kingdom

Chapter 8 Flann O’Brien’s Ulysses: Marginalia and the Modernist Mind

Dirk Van Hulle, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Chapter 9 ‘Truth is an Odd Number’: Flann O’Brien and Infinite Imperfection

Baylee Brits, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 10 ‘An astonishing parade of nullity’: Nihilism in The Third Policeman

Rónán McDonald, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 11 Flann O’Brien and Modern Character

Julian Murphet, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 12 ‘No unauthorized boozing’: Flann O’Brien and the Thirsty Muse

Sam Dickson

Chapter 13 Soft drink, hard drink, and literary (re)production in Flann O’Brien and Frank Moorhouse

Sascha Morrell, University of New England, Australia

Chapter 14 Flann O’Brien’s Aestho-Autogamy

Mark Steven, University of New South Wales, Australia

Chapter 15 Modernist Wheelmen

Mark Byron, University of Sydney, Australia - See more at: http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/flann-obrien-modernism-9781623568504/#sthash.58blLTNi.dpuf

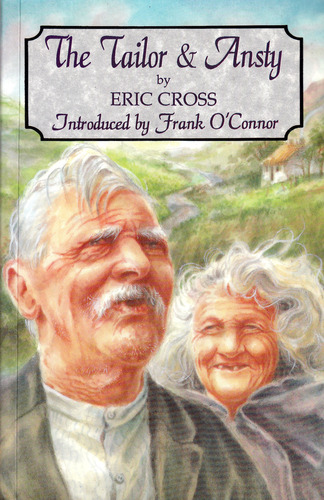

While Eamon de Valera famously judged |"in its general tendency" this 1941 account as ''indecent," years later, the tone of these stories as told by the titular couple from Muskerry in West Cork feels quaint, conveyed from these believers in the fair folk. I found Eric Cross's editorial voice slightly patronizing, as if he was guiding us to a pair of animatronic figures programmed to speak on command their scripted recital. Still, the content, if you can handle the now-antiquated air of the tales told by Tom Buckley and his wife, Anastasia (Ansty).

While Eamon de Valera famously judged |"in its general tendency" this 1941 account as ''indecent," years later, the tone of these stories as told by the titular couple from Muskerry in West Cork feels quaint, conveyed from these believers in the fair folk. I found Eric Cross's editorial voice slightly patronizing, as if he was guiding us to a pair of animatronic figures programmed to speak on command their scripted recital. Still, the content, if you can handle the now-antiquated air of the tales told by Tom Buckley and his wife, Anastasia (Ansty).

While this well-known account has sat on my shelf for decades, I read this only after staying in the author's native village of Dun Chaoin (Dunquin) in the West Kerry/Corca Dhuibhne Gaeltacht. Its prescribed reading for generations of schoolchildren subjected to compulsory Irish has weakened its reputation. I noted when travelling around the Dingle area and her 1873 birthplace that nothing I could see revealed Péig Sayers' presence, although my stay there was too brief, and half at night, to allow me to investigate further. Her book and that of her son are still in print and in local shops, and surely the study of the Blaskets accounts for the bulk of local commemoration, or the scholarship given to her memoir and those of her fellow islanders.

While this well-known account has sat on my shelf for decades, I read this only after staying in the author's native village of Dun Chaoin (Dunquin) in the West Kerry/Corca Dhuibhne Gaeltacht. Its prescribed reading for generations of schoolchildren subjected to compulsory Irish has weakened its reputation. I noted when travelling around the Dingle area and her 1873 birthplace that nothing I could see revealed Péig Sayers' presence, although my stay there was too brief, and half at night, to allow me to investigate further. Her book and that of her son are still in print and in local shops, and surely the study of the Blaskets accounts for the bulk of local commemoration, or the scholarship given to her memoir and those of her fellow islanders. This prolific chronicler's Anglo-Irish background offers a welcome vantage point from which to look back on the half-century (and more!) from the 1916 Rising. Although its subtitle makes this seem as if it ends in 1966, it looks at the cultural changes weakening the Catholic church and the social mores that for long kept many Irish men and women within the sectarian and political divisions that the Free State, Republic of Ireland, and the Northern Ireland province as bywords and manifestations for division, strife, and bitter memories lived out for millions who remained, or left, the fraught island.

This prolific chronicler's Anglo-Irish background offers a welcome vantage point from which to look back on the half-century (and more!) from the 1916 Rising. Although its subtitle makes this seem as if it ends in 1966, it looks at the cultural changes weakening the Catholic church and the social mores that for long kept many Irish men and women within the sectarian and political divisions that the Free State, Republic of Ireland, and the Northern Ireland province as bywords and manifestations for division, strife, and bitter memories lived out for millions who remained, or left, the fraught island.