Here's my review, posted today, to Amazon US about another DNA gene pool plunge, this time by the leader of the National Geographic Society's Genographic Project. My wife and I have to send off our cheek swabs soon for the greater good of humankind. I predict she's K or N1 mDna, and I am R1b Y-chromosome.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/genographic

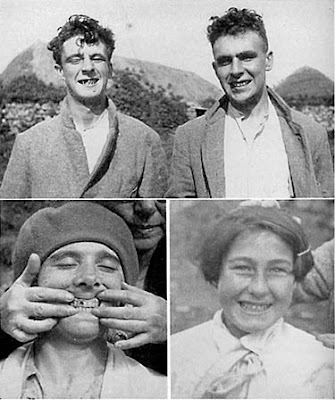

[Image credit. Not much on "deep ancestry" Google image comes up except the boring cover of the book, and eventually a fantastically contentious Wikipedia page full of block, violations, flames, and passion. Reminded me of a Lewis Carroll Wonderland fracas. Or, considering my post last night, how soon an image search for "Jewish Forward" led to antisemitic cartoons by page four. Anyhow, this is from a study by Weston Smith, "Nutrition and Physical Degeneration," reprinted on Gutenberg Books Australia, from a 1930s anthropologist. This is from some dentally bold sharers of my probable R1 haplotype, across the Sruth na Maoile on the Isle of Harris; the best smiles from those on a "primitive" rather than the Sugah i' th' Tae diet. Yesterday also in the Forward issue I read of a reader's zayde who read the Forverts slowly, sipping the "glass tea" while taking, slowly, a sugar cube from a Swee-Touch-Nee tin. He held the cube between his teeth, horse-like, and then drank the tea. The cube dissolving, another took its place. The pages turned. If you are reading this in similar posture but as upwardly mobile grandson of landsman or urban pioneering heiress from bogtrotter, don't spill your g-d damned five-dollar latte on your two-thousand-dollar keyboard.]

Compared to Wells' earlier "Journey of Man" and Bryan Sykes' "Seven Daughters of Eve" and "Saxons, Vikings & Celts," (all three also reviewed by me on Amazon), this is considerably briefer, compressing the genetic information of both mDNA (female-transmitted) and Y-chromosome (male markers) lineages into 250 pp. including a long appendix listing all of the major profiles. Contrasted to the colorfully organized information on the National Geographic Society's "Genographic Project" online site, these appendices largely duplicate the same material in somber typeface. But, having it in book form combined with the previous 175 pp. of text, this makes a concise primer for public and home libraries that, even in our web-dependent age (as you and I know as we read this post!), still need print backup and expansion of material that on the web, as on the NGS site, must be too diffused and remains a bit unwieldy for easy cross-referencing and browsing.

The maps here tend to comment silently upon the material Wells discusses. Unfortunately, Wells more often than not fails to tie his sober, but not altogether dry, text tightly enough to the graphics. You look at the charts and can figure them out, sure, but if the author had taken greater effort in being more explicit, e.g. "see figure 6, where the so-and-so can be seen ranging across the this-and-that at such-and-such a rate," the integration of print and visuals would have enhanced the combined presentation of what can be challenging material for the layperson.

Wells, identified in the author's endnote as a "child prodigy," is ideally placed to write such an introduction to our "encapsulated history," but this efficiently summarized book does feel (as another reviewer commented) as a work in progress. Part of this sensation that much more is going on beneath what can be easily paraphrased for not-specialists may be that the popularization of whats going on in labs now may lag a couple of years behind what only a few experts (Sykes, Oppenheimer, and Wells himself along with possibly Luigi Cavalli-Sforza on a very short list) have the ability to translate findings derived from massive amounts of extraordinarily complex raw material into understandable prose aimed at the general reader.

Bits buried in the appendices demand whole books of their own. I look forward to future volumes about these issues....Half of Ashkenazi Jews can trace their line to four women, and three of those from one "K" group and another "N1." 10-20 people crossed the Bering Strait's landbridge to engender as "Q3" most Native Americans. Click languages may have been the earliest forms of speech. Berbers in North Africa and the Saami ("Lapps") near the Arctic Circle share roots. A non-Asian "X" haplotype is one of the five present among Native American populations; "X2" came not through Siberia but from Western Eurasia. (I wanted to know how this fit into the Kennewick Man controversy, but Wells seems to edge away from debate.) Hitting the Pamir Knot of three mountain ranges connected in Central Asia split up a formerly cohesive Eurasian clan into three main groups as they could no longer move east across that continent's Eastern France-to Korea "superhighway."

Seeing that Sykes has fired off two recent books aimed at the same audience, and that Stephen Oppenheimer also of Oxford (where Sykes taught too) has "The Real Eve" and the new "Origins of the British" in the past few years, now Wells has two. They-- each author having a book around 2002-4 and a second book within the past year) overlap in data and approach, but Oppenheimer appears the most academically dry, Sykes the most eagerly imaginative, and Wells takes the middle ground. No imagined scenarios (unlike Sykes, who by the way has a competing project to gather DNA data) for our NGS leader, but Wells does try with various individuals to make his chosen representatives from today's genetic lines come alive a bit with their own encounters with the data that the NGS finds.

But even this attempt at connecting the world of the test tube with that of those people we pass every day is not carried through enough. The relatively brief amount of discussion given, say, the African American "Odine" who shares Thomas Jefferson's own very rare if not unique genetic marker proves a letdown. Wells builds up the case with flair, but we fail to find enough by that chapter's end to understand exactly where the 3rd President got his genetic marker from and how its rarity in England points to a rather exotic lineage not only for Odine today but any descendant of the Jefferson clan.

In summary, the appendices and a well-chosen short list of suggested books and websites both anthropological and genealogical make this a useful source for beginners wanting a deeper look at their deep ancestry than the NGS site can provide, but not so technical as to bewilder the reader. In passing, Wells is surprisingly reticent about recruiting for the NGS project in his text, but there is an advertisement on the book's final page with information for those who wish to contribute. The NGS by the way uses the funds raised from volunteers here towards a Genographic Legacy Fund that gathers data for free from indigenous and traditional communities, so it's a worthwhile cause.

I would have liked to know more about how, if Wells studied with Luigi Cavalli-Sforza for his doctoral work at Stanford, or if Wells presumably worked alongside geneticists Oppenheimer and Sykes at Oxford, how his own project and conceptualization of how the DNA research could be used differed from his eminent mentors. (As an aside, Sykes in his recent "Saxons" book never mentions Oppenheimer who I assume is just down the hall from him at Oxford!) Cavalli-Sforza with his HGDP and Sykes with his company Oxford Ancestors appear to have slightly divergent goals from the NGS study, and I remain a bit unclear about where the three DNA-gathering enterprises cooperate or whether they are all amassing their data separately. Wells hints a bit about HGDP, but does not mention Sykes' company. I suspect that the whole scientific and enterprenuerial venture's combined story here may have to wait another half-century, when an elderly Wells (he's well under 40 now!) composes his memoirs.

No comments:

Post a Comment