As with his previous books for the "educated reader" looking for a light but worthwhile introduction to philosophical and moral issues, Alain de Botton relies upon a mix of photos and illustrations with witty or profound captions to lighten the heavier lessons of his text. He glides over as much as he digs into.

Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer's Guide to the Uses of Religion indicates by its subtitle the utility to which he puts beliefs and rituals. Whether this fervent application of Photoshop and pious belief in the transformational potential of humanism will find many converts, given its erratic and at times superficial coverage of issues and ideas, remains as open-ended as its contents. These direct the seeker to secularize ancient stories and venerable practices in the therapeutic service of one's own growth and that of the community, bereft of belief in a higher power.

Born in England to a family of Jewish ancestry but one lacking personal investment in its spiritual inheritance, de Botton respects the cultural legacy and virtuous examples inculcated by religion. He contrasts his gentler skepticism with the harsher diatribes of prominent neo-atheists. Instead of damning the damage done in the name of faith, de Botton urges a mature acceptance of the benefits religion has given people in the past. By applying ethical lessons in short but sprawling chapters organized around a righteous virtue or moral principle, he encourages skeptics and non-believers today to learn from centuries of religious experience in dealing with human limitations.

De Botton begins by listing the reasons humans invented religion: to live in communities while overcoming selfish and violent impulses; to cope with pain--caused by our failures, troubled relationships, and the death of loved ones--and to face "our own decay and demise." (9) This short study, the size of a prayerbook for a secular aspirant, serves as inspirational reading for those who may admire some elements of sacramental rituals, Zen tea ceremonies, or Torah readings, but who cannot believe in them as other than inventions of our ancestors to explain or interpret the mysteries around us.

The first chapter argues for reversing the societal "process of religious colonization" to claim its moral legacy and cultural richness while separating secular identity from religious rituals and beliefs, thus to enrich "our soul-related needs" (13). De Botton refuses to discard the lessons of religion along with its encouragements and prohibitions, for religion’s enduring impacts can teach us how to live better. By burning off the residue of an outmoded set of dogmas and doctrines, he seeks to distill the essence of what can nourish a non-believer.

Next chapter, bonding gains analysis. The comfort of the Catholic Mass, a Passover meal, Yom Kippur’s congregational confession, and the upending of the medieval Feast of Fools are all examined skillfully as communal rituals uniting and enriching us. The satire of the last example channels the playful nature underlying games and rules which humans create. People need to letting loose rather than restraining sillier impulses. De Botton proposes a standardized framework that allows tension to be released now and then. He imagines, as he inserts altered photographs throughout this volume, the opening of an Agape Restaurant able to satisfy the culinary and communal longings of its non-churchgoing clientele.

De Botton reminds us of how religions cement people together, whereas modernism tends to isolate them. Reflecting on the appeal of paternalism and guidance rather than a vain libertarianism elevating individual gain above all other priorities, de Botton remarks how reform can come from efforts which involve others. "Religions understand this: they know to sustain goodness, it helps to have an audience." (39) Chapter Three explores the continuing need for direction, if not from heaven, than from the angels of our better nature. While atheists lament the imposition of scriptural injunctions in public spaces, they overlook their own complicity in encouraging the relentless promotion of consumerism and consumption, in ways as damaging to modern sensibilities as the outmoded frames of traditional reverence which secular adherents disdain.

Chapter Four contrasts secular education's ambitions that cultural events and literary studies may supplant spiritual searches. De Botton also confronts the lack at the heart of university preparation which stresses careers over insight, and which divorces the improvement of the soul from soulless practicalities for the job-seeker. He suggests that re-reading texts and repeating rituals, as is done in the yearly cycle of Torah readings or the Zen tea ceremony, might serve as models for secular instruction aimed at inculcating lasting, as incremental and lifelong, alteration of one's outlook and one's relationship with the self and with others.

He then powerfully speaks to what atheists deny: our frailty when nobody is there to comfort us as flailing adults. The fifth chapter discusses eloquently the need fulfilled by Buddhist or Catholic models of maternal compassion. He wonders if "Temples to Tenderness" might not replace shrines and statues for those moored within an uncaring world. Earlier, he noted how hard it may be to take solace from our common humanity when enduring the crush of people on Oxford Street or the airport terminal, and here, de Botton reminds readers of the coldness of modernity, and the timeless appeal of being held, caressed, and soothed.

The following chapter praises another quality inherited from religious tradition, that of pessimism. Secular people today tend to be more optimistic than believers, a reversal de Botton notes from past patterns. The admonition "why can't you be more perfect?", he adds, may be more common in marriages between those who lack Christian or Jewish beliefs. These insist on stability more than happiness as the prerequisite for an adult relationship that will endure as a partnership to perpetuate and direct the ongoing family. Secular people, by comparison, may flee fidelity. They pursue their own ideals and dreams, chasing an elusive fulfillment. Modern people need, he concludes, a Wailing Wall to share and shove the little messages of our problems into perspective, amidst fellow sufferers.

He pithily summarizes the anguish within the Book of Job and Baruch Spinoza's philosophical constructs, both of which tried to place human despair within a universal perspective. De Botton turns to vast space seen by the Hubble telescope today as a corrective for our own myopic era. Chapter Seven reminds us of how puny any earthly ambition or failure registers when set within such an immense panorama.

Then, de Botton adjusts his scrutiny. He wonders what happens when religious works, sold or stolen from their chapels or temples, adorn modern museums. How can art, for a patron, speak to a century where few kneel before reliquaries or relics in churches empty of the faithful who once filled them in an older Europe? Atheists might be inspired, de Botton proposes in Chapter Eight, to erect an atelier of modern artists "depicting a Seven Sorrows of Parenthood, a Twelve Sorrows of Adolescence or a Twenty-one Sorrows of Divorce." (I am not sure how many will rush to contemplate such monuments to desolation, on the other hand.) De Botton examines for instances of popularized sympathy examples from Christian art and contemporary photography, and he repeats in one caption his moral: "what separates indifference from compassion is the angle of vision."

Visualizing within a wired age, we have only our feet to gaze at, De Botton avers, not our concrete jungles and stucco canyons. Perhaps we can appreciate why monasteries were invented. After all, Protestants bear the blame for modern architecture. That is, they denuded church interiors, and stripped buildings down to austere dimensions. Modern cities and suburban landscapes attest to this imposed sense of being made to "feel small". De Botton suggests in his ninth chapter a remedy to such diminished dimensions. Temples to Perspective might show us how humans fit, although our hominid era albeit may be barely visible, into the towering scheme of time and space, and this might restore a humbling sense of our dimensions in the cosmos.

With their reliance on modest reason rather than pious elevation, secular intellectuals, de Botton observes of his earnest colleagues, usually lack the historical or cultural advantages afforded their religious counterparts. The unbelievers as "volatile individual practitioners run what are in effect cottage industries, while organized religions infiltrate our consciousness with all the might and sophistication available to institutional power." De Botton contrasts the scholarly success of Thomas Aquinas in a popular career against the obscurity endured by Friedrich Nietzsche during his life in support of this argument. This appears, however, to skim over the neo-atheist appeal of Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens among audiences. De Botton aims this volume at overcoming the weaknesses of this cabal, but he exaggerates the difficulty of secular proponents finding a ready audience and warm welcome in person and via many media.

While de Botton understates the role in the century and more since Nietzsche of tenure, talk shows, and an occasional book to spark controversy (at least for a few media-savvy competitors to de Botton--although his own accessible but erudite works have gained him far more acclaim than those of most philosophers these days), one notes how inspirational volumes often top American lists. Consider one of the past year's most persistent number-one titles, a toddler's testimony Heaven Is For Real “as told to” his father (an evangelical pastor in Nebraska), about the not-quite-four year old's meeting--after an appendectomy gone awry--with Samson, John the Baptist, and a blue-eyed Christ. Nearby on the bestseller charts, self-help nostrums adapt conventional pieties as marketed for niche Christian, New Age, and/or business-oriented audiences.

Commodification has its benefits, as religions organized around easily recognizable symbols, icons, and rituals verify. The author encourages secular proponents to transmit their views more forcefully and cleverly, to compete by campaigns of wise and witty branding. He intersperses mock-ups of these throughout his volume. Despite de Botton's earnestness and wit, these altered images may provoke mockery or parody rather than convey comfort or inspiration.

Its American dust jacket features a paper imitation of a leather bound bible. What Sartre called a "god-shaped hole" provides a clever depiction of the existentialist audience primed for its preaching. The title nestles inside the void opened up by the cut-out, and the burnished letters of Holy Writ, half-visible, half-excised, symbolize de Botton's mission: to accept the possible limits of humanism without discarding the cost-benefit equations tallied up over thousands of years of religious practice.

He wraps up this brief handbook with a nod to his "only intermittently sane" ideological forebear, Auguste Comte, who in the early nineteenth century established a template for, and hoped for temples to, a Religion of Humanity. However, as de Botton admits, Comte's rational replacements for religion failed to inspire but a few of his French heirs to separation of Church and State after revolution and the Enlightenment, a consequence this author may underestimate as a cautionary tale. Visitors to Notre-Dame vastly outnumber those to any shrine to Comte's ambition. Granted, worshipers at such cathedrals usually are dwarfed by tourists, while parishes and shrines languish; de Botton's European perspective neglects the megachurch phenomenon popular in the U.S. and increasing in the Third World.

De Botton acknowledges the difficulty of constructing such a rational, but inspirational, effort, when religions have centuries if not millenniums of a headstart on human habits. Still, he reminds his readers at the close of this diligently illustrated, devotedly skeptical, but ultimately encouraging guide: "Religions are intermittently too useful, effective and intelligent to be abandoned to the religious alone." This curious, if cautiously phrased, conclusion sums up this message of this philosophical heir to Comte and centuries of dogged rationalists who seek the solace of a higher power: as a force for inspiration generated from our own ambitions, dreams, and longings. (As above, shared on

The Pensive Quill 12-9-12; Edited and shorter version to

Amazon US 3-5-12; 3-8-12 at

PopMatters)

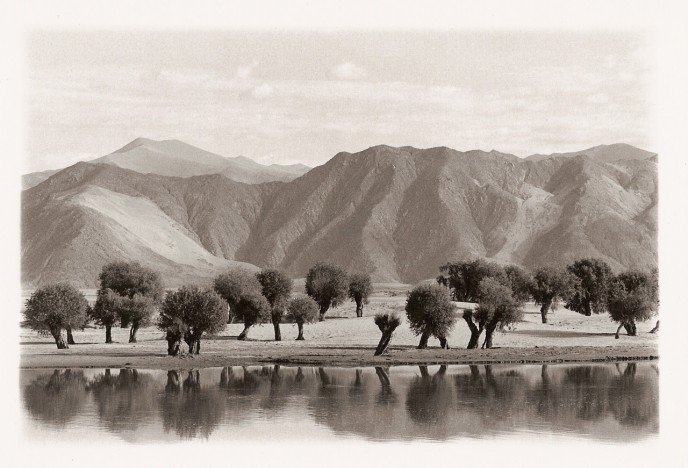

...reminds me also of visions as if glimpsed by Coleridge, Calvino, or Borges, of impossible cities beyond our comprehension. One impossibility is assuming such places will stay this way. When the Maoists overthrew the kingdom of Nepal in 2008, so went the last king of Mustang. As the new regime courts the Chinese, tourism and modernization will follow as inevitably as Kathmandu's made filthy by Israeli and German trekkers and Lhasa by military-owned brothels, neon, Holiday Inn, and every manner of cynical exploitation. Such realms contract and dry up, pressed between China and India, and a Nepalese effort to supplant Buddhist fastnesses with Hindu-dominated enclaves where monasteries may turn more museums.

...reminds me also of visions as if glimpsed by Coleridge, Calvino, or Borges, of impossible cities beyond our comprehension. One impossibility is assuming such places will stay this way. When the Maoists overthrew the kingdom of Nepal in 2008, so went the last king of Mustang. As the new regime courts the Chinese, tourism and modernization will follow as inevitably as Kathmandu's made filthy by Israeli and German trekkers and Lhasa by military-owned brothels, neon, Holiday Inn, and every manner of cynical exploitation. Such realms contract and dry up, pressed between China and India, and a Nepalese effort to supplant Buddhist fastnesses with Hindu-dominated enclaves where monasteries may turn more museums.