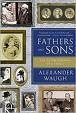

This collective biography spans about six generations responsible for, one from the fifth generation tells us, about 180 books-- quite an average. Alexander's narrative depicts The Brute, muttonchopped patriarch from the 1860s; Arthur, Pickwickian declaimer; Evelyn & Alec, one funny, one feckless, both novelists, bon vivants, and diligent scribblers; Auberon ("Bron"), satirist whose entries for the Daily Telegraph & Private Eye I'd always heard of but never before (given their London provenance) had the chance to sample-- in his son's excerpts here; Alexander, who never seems to have been called as such ever by Bron. "For the first eight or ten years of my life I was addressed simply as 'Fat Fool'." (422) It's that kind of relationship; the book concludes gracefully if ruefully with the newest father's glance at his next generation. Alexander, as I must call him for clarity's sake in a book with three Brons and a He-Evelyn & She-Evelyn, delves into the correspondence, rumors, anecdotes, novels, journalism, and gossip that makes up about a century and a half of alternately engrossing and trivial material.

This collective biography spans about six generations responsible for, one from the fifth generation tells us, about 180 books-- quite an average. Alexander's narrative depicts The Brute, muttonchopped patriarch from the 1860s; Arthur, Pickwickian declaimer; Evelyn & Alec, one funny, one feckless, both novelists, bon vivants, and diligent scribblers; Auberon ("Bron"), satirist whose entries for the Daily Telegraph & Private Eye I'd always heard of but never before (given their London provenance) had the chance to sample-- in his son's excerpts here; Alexander, who never seems to have been called as such ever by Bron. "For the first eight or ten years of my life I was addressed simply as 'Fat Fool'." (422) It's that kind of relationship; the book concludes gracefully if ruefully with the newest father's glance at his next generation. Alexander, as I must call him for clarity's sake in a book with three Brons and a He-Evelyn & She-Evelyn, delves into the correspondence, rumors, anecdotes, novels, journalism, and gossip that makes up about a century and a half of alternately engrossing and trivial material.Rather than the Delphic oracular injunction to "know thyself," Alexander avers this on the lowered level of the teenaged "I need to discover the real me." He counters: "Perhaps 'O Man, know thine ancestors' would be a more useful motto for the modern egotist to pin on his puffed lapel. For the key to his identity, if such a thing even exists, will be found to lie not where he instinctively looks for it in the mirror-glass in front, but furtively concealed all about the hedgerows and borders of the long, twisting, dusty road behind." (19)

Why focus on the fathers and sons? That's where the bulk of the literary material lies, and the reason for "Wavian" renown, envy, backlash, and retribution. Michael Dirnda's review posted on Amazon recounts the episode of Bron's Cypriot machine gun gone awry, and this could have been lifted from a novel by Evelyn, his father. Alexander's best when he shows precisely how real life overlapped with Evelyn, Alec, Arthur, and Bron's own writing, and how they all used extraordinary wit (at their best at least; all wrote so much that inevitably standards slipped) to illuminate in fiction and essays their own foibles and those of their fathers. This pattern, as the son reflects late on in this family history, presents fascination and difficulty.

"A father may have many children to add to his many concerns but a son has only one father, the 'august creator of his being', who chooses where he lives, where he goes to school, what he might find funny and, to a certain extent, what he thinks. Fathers are more important than sons, and therein lies the problem." (418) The gist of this lengthy book, filled with letters back and forth between the generations as they snipe, nudge, and snicker with each other, is that in such a chain of progenitors and offspring may not lie conventionally false notions of affection for children-- in all their boredom, annoying habits, and demands to Be Taken Seriously. Instead, refreshingly, each father W. appears to-- as documented closely here-- have detested and escaped from his snivelling progeny whenever possible, and for this, in time if decades later, the son loved the father. Such honesty, as Alexander and his father show, eviscerates sentiment. It attacks maudlin convention of how parenthood should be celebrated, and this remains the lasting message I take from this book.

But I'd be remiss to say, without giving away the best parts of this narrative, that for all the longueurs, for all the endless moaning about headmasters and contracts and affairs and alcohol that occupy so much of the content of the letters and the recollections-- that considerable learning, outrageous incidents, and genuine humor at the foibles of our fallen human condition provide the essence of this study. Evelyn and Bron sigh eloquently, in frustration at the pablum that the nanny state thinks we need for nourishment in ever more philistine times.

Not all is either stultifying correspondence, insider family lore, or dutiful corroboration or refutation of allegations whispered or thundered for decades against the Waughs. The contents are stuffed full of epistolary invective, and it's probably difficult for Alexander, having to set the record straight and add his many askew angles to what's been printed and promulgated about his family, to edit the wealth of primary sources he presents, sifts, and challenges. The book may suffer in readability for those of us not as enamored of or as intimately related to Waviana. Still, this is a forgivable fault and a welcome one, given the access Alexander offers for those who immerse themselves in his in-depth presentation of Alec, Arthur, and his own father.

By contrast, the more familiar Evelyn recedes, and we see him more as one integrating his father, Arthur, into such works as "A Handful of Dust" so memorably. Evelyn's more personally presented to us, and less of his works or public life, such as it was, gains scrutiny here. The book, for me, gains poignancy in the later years of Evelyn and the maturity of Bron; this allows Alexander more space to consider his own entry then onto this crowded dais of literary predecessors. His emphasis is on the personal side of Evelyn, his grandfather, as he signed to Bron "yours affec. E.W."

Bron comments on Evelyn after his death that "politics bored him. His interest was confined to resentment at seeing his earnings redistributed among people who were judged more worthy to spend them than he." (qtd. 424) This typifies an ethical, yet bitter, sense of withheld fairness amidst what Evelyn lamented as the "abominable difficulty of human relations." Bron credited Evelyn's removal of all his teeth without anesthetic as improving his disposition in old age; Evelyn in turn had followed Arthur's venerable example. Such relationships, then obliquely reflected by Bron with Alexander, as had Evelyn & Alec's with Arthur, sets up a hall of mirrors. The later father and son characterize themselves as "liberal anarchists," fed up with a notion of prosperity that insists only on materialism and gadgets. (Although I did marvel at Bron's ability "without gainful employment" at 24 when fathering Alexander "near Treviso in Italy at the house of a one-eared Arabist called Dame Freya Stark" to "employ a daily help, a French maid and a maternity nurse." (422-23) Money did seem to afford handsome estates, lengthy trips abroad, boarding schools and Oxford, and lots of fine wine on what appeared to me vanishingly little visible means of income. This may be my American sensibility, unaccustomed to how the other half lives.

Alexander on Bron: "He, too, used his writing to free himself from the irritations of life and the problems of human existence." (430) The whole refusal to kow-tow to the demands of children, while delighting in the pursuit of one's own selfish pursuits, certainly runs against the prevailing philosophy of our age. Somehow, the Waughs managed to produce the children they deserved, I suppose. This all reminds me of an observation by Borges: both mirrors and procreation are abominable, for they reproduce the human figure without reason.

Bron emerges as a match for Evelyn when it comes to insight beyond the family's eccentricities and social shenanigans. As Evelyn became discouraged by the post-Vatican II Church, so did his son. After attending services that Bron realized "would be completely unrecognisable to him, that the new religion had nothing whatever to do with the church to which he had pledged his loyalty," Bron "felt I could distance myself." Wisdom follows: "Whatever central trut survives lies outside the modern church, buried in the historical awareness of individual members. Or so it seems to me. But whenever I have doubts, it is my father's fury rather than divine retribution which I dread." (435)

Bron's son follows suit. He titles a recent book "God," yet asserts that the loss of a True Faith (as Evelyn famously displayed) may be simply proof that the zeal of the convert's rarely hereditary. Decline & Fall repeats each generation on the Waugh's domestic stage. "The English show their hatred for children by dressing them in anoraks and romper suits, stuffing them with sweets, refusing to talk to them and sending them out of doors whenever possible in the pathetic hope that someone will murder them." (qtd. 437) The clumsy love of father for son, and the half-shameful, half-affectionate fumble of emotions, moves through many letters quoted here, if to often unintentionally comic rather than the usually desired risible or denunciatory effects.

A couple of examples must suffice. Arthur wrote to teenaged Alec off at school, in May, 1914 about the sin of self-abuse. "It is an awful thought that someday you might take to a poor girl's arms a body that will avenge its own indulgences upon children yet unborn." The letter goes on, by the way, for probably over fifteen hundred words, and is printed in its entirety. I do doubt the assertions in one footnote Alexander adds, however, so I must append it too for the sake of transparency: "Masturbation was not considered unhealthy until 1710 when John Martens, a quack doctor and pornographer, proclaimed it as such in a book called Onania. Marten's fortune derived from the medicine sold in conjunction with his book. The Church did not consider masturbation a sin, or indeed link it to Onan's behaviour in Genesis, until after the publication of Onania." (63) Certainly a topic needing hands-on research?

There's much of this sort of skewed erudition here from all Wavian contributors. I leave to you to burrow out the derivation of Crutwellism, to hearsay regarding Oxonian "dog sodomy," Evelyn's providing rabbits with a deadly glass of Christmas cheer, and his wife Laura's fate when she fails to get rid of rotten fruit. You'll find which Waugh died with a turd near his corpse, which one provided inspiration for both Island Records and the cocktail party, which one became Colonel Gaddafi's favorite author, and which one was depicted in a moralizing portrait, "Dr Waugh and the Perverse Pupil." Not to forget such sentences as this, concerning "an ethnic guitar" which Alexander's brother Nat brings back from South America "as a present for his mother-in-law" that "contained chagas larvae, which hatched unto beetles, crawled out of the instrument, killed the dog and rendered his mother-in-law insane." (443)

(Posted to Amazon US today.)

No comments:

Post a Comment